Over the next eight years, even as Obama went up for a second term, Peter didn’t think too much about politics; he voted one more time, in the 2014 district attorney’s race in Bexar County, because some friends were working on the challenger’s successful campaign. It wasn’t until after Donald Trump’s election, in 2016, that he started paying more attention. “I just personally never liked the guy, and I was shocked to see that he was going to be our president,” he says. He began to ask himself: “Why is it good to be a Democrat? Why is it good to be a Republican?”

Peter didn’t know what either party stood for. Friends and family told him that based on his values, he was probably a Democrat. But he wasn’t sure what being a Democrat meant. So he began talking to the only person in his immediate family who did follow politics: his mother-in-law, Josette Salazar. He started watching the news on television and looking up CNN and New York Times stories on his phone apps. In July of last year, as he and his wife, Angel Marie, were waiting for the birth of their first child in the obstetrics ward of Southwest General Hospital, he and Josette watched hours of the Robert Mueller hearings together. Josette provided a running commentary that drew him deeper into the drama unfolding on the screen. She insisted to him that his vote mattered, and she urged him to vote again. As of this year, however, he still hadn’t. “That’s the thing,” he said, “I love reading about politics, I love watching it. But I haven’t been convinced to actually go out there and vote.”

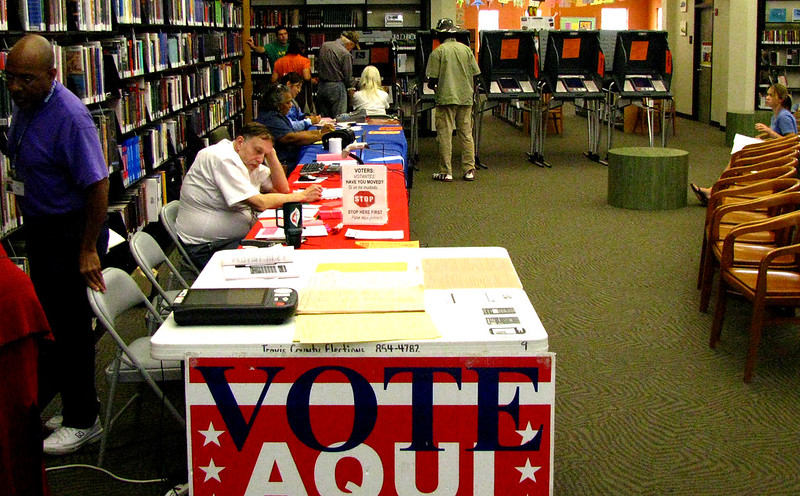

Peter isn’t alone. The question of why more Latinos aren’t voting has consumed politicians, pollsters, and political observers for the past few decades. Latinos make up about 30 percent of Texans who are eligible to vote but, in recent elections, only about 20 percent of those who actually cast a ballot. To be sure, Latino voter turnout has been increasing steadily. But Latinos’ presence at the ballot box still falls short of its potential. Next year, they are projected to become the largest demographic group in Texas. If they were to turn out in larger numbers, they could swing election outcomes in the state and—given Texas’s large role in the electoral college—at the presidential level too. This is the proverbial “sleeping giant” that, again and again, liberals have hoped will help them turn Texas blue.

But is “sleeping giant” the right metaphor to describe Latino voters? Are they really as disengaged as that phrase suggests? Or are there deeper reasons why many of them don’t vote? And, among those who do vote, why don’t more of them vote for Democrats, as liberals would like—and why are many voting for Donald Trump, a politician who has spoken of Mexican and Central American immigrants as murderers and rapists and as a serious threat to Americans?