How the Spanos Family Built a Fortune Selling Bologna Sandwiches to Mexican Farmworkers

*Why you should read this: Because a family worth $2.6 billion is asking the City of San Diego, with 1.4 million Latinos – 35 percent of the population, to use public money to construct a stadium for their team, the Chargers. Because the Spanos family started the business that built its fortune by selling bologna sandwiches to braceros in the 1950’s. VL

By Ry Rivard, Voice of San Diego

There are “no poor football team owners,” as a spokesman for the Chargers recently put it.

Indeed.

The Spanos family, which owns the majority shares of the Chargers franchise, is worth $2.4 billion, according to Forbes.

As the team lobbies for public money to subsidize a new stadium and convention center, the Spanoses’ wealth has come under scrutiny: Why, people ask, should San Diego taxpayers use billions in public tax dollars to support billionaires?

Less understood is where the family fortune came from. Alex Spanos, the family’s 93-year-old patriarch, once had nothing but ended up building a real estate empire. How? To build great wealth, you have to first build up some money – capital – you can later invest.

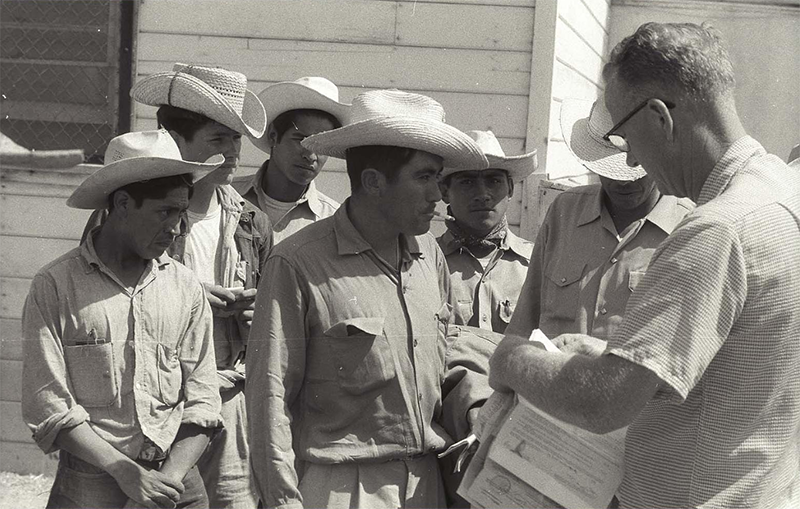

For Spanos, it started with bologna sandwiches and Mexican farmworkers. The family has long faced questions, in fact, of whether Spanos helped exploit farmworkers in the notorious Bracero program that started nearly 70 years ago.

Spanos himself tells the story in his autobiography “Sharing the Wealth: My Story.” This is how it all began:

In summer 1951, Alex Spanos – the son of a Greek immigrant – was both jobless and a father of two.

He borrowed $800 from a bank to start a catering business in his hometown of Stockton.

He saw demand from a new wave of migrant farmworkers circulating through the Central Valley. They were known as “braceros,” Spanish for laborers, and they were coming to harvest crops as part of a series of formal immigration agreements between the United States and Mexico.

Read more stories about the bracero experience in NewsTaco. >>

Between 1942 and 1964, nearly 5 million of these Mexican workers came to do seasonal work in the United States. Initially, they were invited in because American men were off fighting World War II. By 1951, with the war over, American farmers had come to depend on the foreign workers.

At first, Spanos said he simply wanted to be a sandwich peddler, selling to workers during their breaks. He used the bank loan to buy a truck, a slicing machine, a meat cleaver, bread and the cheapest meat he could find – bologna.

Do you like stories that reflect authentic latino life in the U.S.?

Be part of a positive change.

Ry Rivard is a reporter for Voice of San Diego. He writes about water and land use. You can reach him at ry.rivard@voiceofsandiego.org

[Photo courtesy of the Leonard Nadel Photographs and Scrapbooks, Archives Center, NMAH, Smithsonian Institution]