At a Border Patrol station in South Texas, two agents cuffed Jeelani Ghulam’s wrists and ankles and led him toward a waiting bus with barred windows. The cuffs were painfully tight. He shuffled down the aisle, took a seat and waited. As a 20-year-old refugee from Pakistan, he knew nothing of the system that was about to swallow him. When the bus approached its destination, he noted with shock the barbed wire that topped the fences along the perimeter. “Oh my God,” he said to himself.

At the South Texas Detention Complex near Pearsall, he was issued a prison-style jumpsuit and bedsheet. Then a guard — an employee of the private prison corporation GEO Group — led him to his new home, a dorm-like room holding 100 detainees. He jumped as the heavy metal door slammed shut behind him. “In detention, everything’s a cage,” Ghulam later told me. “I saw a bird outside one time, and I thought: Even the birds and animals are free, but the humans are detained. What has happened to the world?”

America wasn’t supposed to be like this. In late 2009, Ghulam fled Pakistan after someone close to him was killed, and he received death threats over an aspect of his identity. (Ghulam asked the Observer not to disclose the details out of fear of retaliation.) He flew from Pakistan to Brazil and then traveled for nearly a year by foot and bus through 10 other countries during his journey to the United States. In Ecuador he sold incense on the streets for travel money; in the Panamanian jungle he was bitten by a snake and nearly died.

“I WAS YOUNG AND STILL THINKING LIFE WILL ONE DAY BE VERY BEAUTIFUL. BUT IN DETENTION, I AM LOSING HOPE.”

In November 2010, he finally made his way to the U.S.-Mexico border and hired a coyote to ferry him over the Rio Grande in a small boat. After the crossing, the smuggler pulled a knife on him and demanded more money. When Ghulam refused, the smuggler lunged; Ghulam raised his arm to protect himself and was stabbed in the hand. Bleeding and afraid, he handed over the money he’d hidden in his jacket’s inner pocket, and the coyote abandoned him to the South Texas brushlands. He wandered aimlessly for three days, and when Border Patrol agents found him, it was more rescue than apprehension. He told them the story of his harrowing journey. Ghulam was seeking political asylum, but he would soon find himself in a jail cell.

Ghulam spent six months in detention, where he says he suffered constant cold, hunger, sleep deprivation, verbal abuse from guards and inadequate access to legal counsel. Immigrant advocates have called the South Texas Detention Complex “infamous for its harsh conditions,” and several reports have documented sexual abuse of detainees by guards, use of solitary confinement, and inadequate medical care resulting in at least one death. Such conditions persist despite international conventions signed by the United States that safeguard asylum seekers’ rights to “personal liberty and freedom of movement” and narrowly limit states’ rights to detain them.

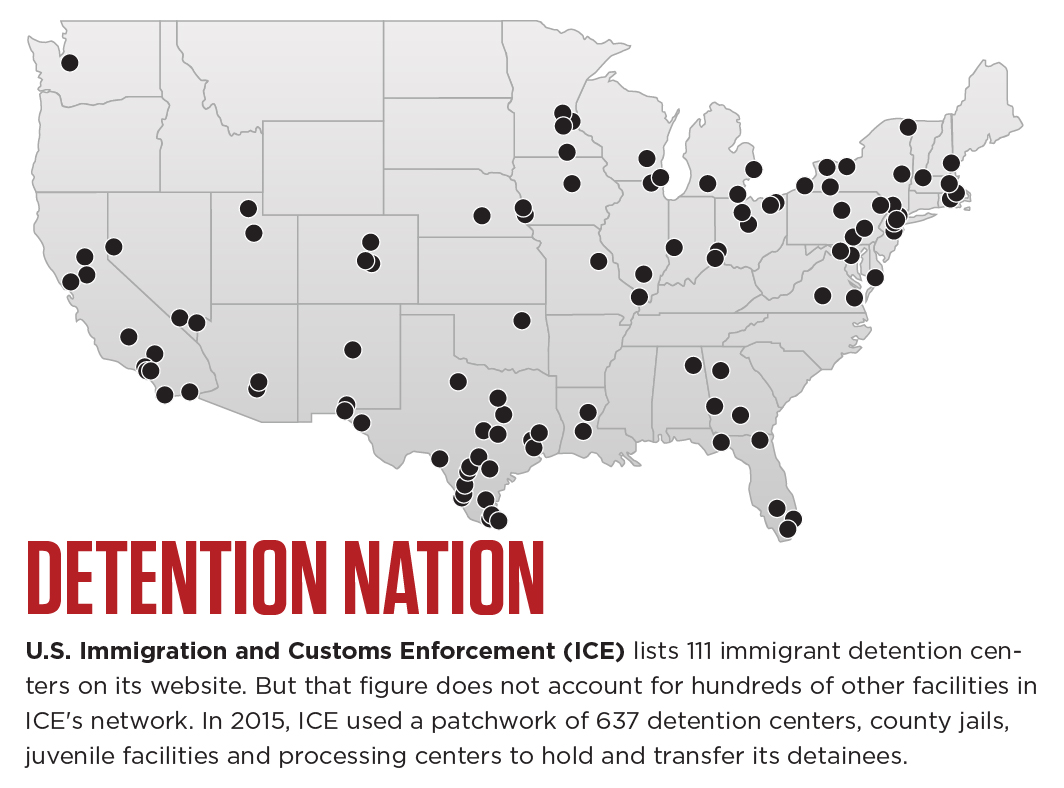

Ghulam’s experience is far from unusual. In 2015, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) held on average about 33,000 immigrants in detention each day — a 1,550 percent increase from an average of 2,000 in 1980, according to the American Civil Liberties Union. (This October, the number of detainees hit an all-time high of more than 42,000.) The detainee population includes thousands of asylum seekers like Ghulam, who move through an ever-shifting patchwork of public and private holding centers. Texas is the epicenter of this detention system, with 23 detention centers accounting for 30 percent of total detainees and 45 percent of detained asylum seekers.

Detention centers are black holes for legal access, with only 14 percent of detained individuals obtaining legal counsel — compared with 69 percent of those released. Many immigrants will languish in detention for months or even years, since there is no legal limit on how long some of them can be detained. (In what may be a landmark case, the U.S. Supreme Court is considering whether it’s constitutional to detain immigrants for longer than six months without a bond hearing.) And most starkly of all: Since 2003, according to ICE statistics, at least 166 immigrants have died while in detention, often due to medical negligence or failure to prevent suicide.

Ghulam says his time in detention took a psychological toll. “I was young and still thinking life will one day be very beautiful,” he told me. “But in detention, I am losing hope.”

Ghulam is 27 now, and when I meet him, he sports a stylish amount of stubble and is dressed sharply in a black leather jacket. He speaks in long stretches, and smiles often. But his steady voice turns indignant when he talks about detention. “They treat us like we are big criminals,” he told me. “Like people who did some serious crime.”

Ghulam was born into a well-to-do family in Pakistan and was a university student when he fled his country, leaving behind four siblings, his parents and his studies.

Detention was rough on him. He remembers a guard once telling him he’d never get out because he was a “Muslim terrorist” — a bitter irony since Ghulam is agnostic. And the kitchen provided trays of food he said were one-fourth or one-fifth of a sufficient meal. He also worked in the kitchen, scrubbing large pots and pans for $3 a day, which he spent on additional food from the overpriced commissary to quell his constant hunger. Generous by nature, he shared the noodles and tea bags with his fellow inmates. After tea, Ghulam would try to sleep, huddled under the paper-thin blanket he was issued. With the air conditioning kept unbearably high, he shivered through the night.

“THEY TREAT US LIKE WE

ARE BIG CRIMINALS. LIKE PEOPLE WHO DID SOME SERIOUS CRIME.”

U.S. taxpayers foot the bill for this detention system. The average cost per day to detain an inmate is $126, according to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. That means it costs around $23,000 to detain an immigrant for six months. GEO Group earned $84.50 per day for Ghulam’s detention — about $16,000 over the course of his six-month incarceration.

ICE’s detention budget has nearly tripled from $864 million in 2005 to the $2.2 billion it plans to spend in fiscal year 2017. The ballooning cost tracks closely with the federal government’s widening migrant dragnet, which has swept up a broad array of people, including pregnant women, families with children, and longtime residents arrested for minor crimes.

Things haven’t always been this way. As recently as 1995, the United States detained one-fifth of the migrant population it detains today. The shift toward mass incarceration began in earnest in 1996 when President Bill Clinton signed two laws: the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act and the Illegal Immigrant Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, which together greatly expanded the number of immigrants subject to mandatory detention.

President George W. Bush then oversaw another expansion after 9/11 when he formed the Department of Homeland Security, reframing immigration as an issue of national security. As a unit of the new department, ICE initiated “Operation Endgame,” which had the goal of “ensuring the departure from the United States of all removable aliens.” President Barack Obama has continued to feed the system with record-breaking deportations and, since 2014, skyrocketing detention of asylum-seeking families.

The pursuit of profit has helped drive the explosive growth of immigrant detention. Today, ICE holds nearly 75 percent of detainees in privately operated facilities. In 2015, the two largest private prison companies, GEO Group and Corrections Corporation of America (recently rebranded as CoreCivic), each earned nearly $2 billion in profits. Since 2009, Congress has padded those companies’ bottom lines by requiring ICE to maintain at least 34,000 detention beds at any given time. For prison corporations, a detained immigrant is a profitable immigrant.

At this point, he could have been released on bond with a notice to appear at a future court date. He would have qualified for a temporary work permit. But, in order to be released, a detainee must have a sponsor — someone with legal status in the country who can take the person into their home. The sponsor must send a letter promising that the detainee will show up to their next court date. With no family or friends in the United States, Ghulam’s chances of landing a sponsor seemed slim.

WITHOUT A LAWYER, AN ABYSMAL 2 PERCENT OF DETAINED IMMIGRANTS OBTAIN SUCCESSFUL LEGAL OUTCOMES.

As the days ticked by, he felt increasingly alone. He remembers lying on his bunk in his cell, wearing his dark-blue prison uniform — the color indicated that he was a low security threat — and listening for the voice of one of the ever-present guards. A few evenings a week, a guard would call out the bed number of one of his roommates and escort the man outside, the heavy metal door slamming shut behind them. Ghulam learned quickly that he would never see the person again. Many were deported. His natural good humor dwindling, Ghulam cringed each time he heard the guard’s voice.

About a month into his detention, Ghulam had his first hearing with an immigration judge. Like 86 percent of detainees, Ghulam had no lawyer. Because immigration court is technically a civil proceeding, migrants aren’t entitled to an attorney. Gaining access to counsel in detention is extremely difficult. Detainees are isolated and unable to earn money, and the prison companies often fail to alert people to their rights. Without a lawyer, an abysmal 2 percent of detained immigrants obtain successful legal outcomes. Luckily for Ghulam, his judge set another hearing date and instructed him to find representation.

With no money and no way to earn any, Ghulam asked an Indian detainee who was about to be released to contact Ghulam’s father in Pakistan. Through a circuitous route involving a family friend in Greece, the Indian man procured $1,500 from Ghulam’s father and hired a lawyer for Ghulam.

Ghulam thought his legal troubles were over, but they’d only just begun. He would soon find out that detained migrants, isolated in far-flung rural detention centers, are the perfect targets for unscrupulous attorneys. Desperate and unfamiliar with the American legal system, they often fork over cash to lawyers who do sloppy work or no work at all.

Ghulam met briefly with his lawyer’s assistant, who instructed him to request a bond but offered no help in finding a sponsor. The assistant also helped him file his asylum application but made numerous factual errors, including Ghulam’s date of birth, and failed to help him gather additional evidence to support his case.

Then, when Ghulam’s second hearing came around, his lawyer simply failed to show up. He wasn’t at the third one, either. Or the fourth. Ghulam would never lay eyes on his attorney.

At the fourth hearing, the judge gave him a final opportunity to find adequate legal counsel and avoid having to represent himself.

By now it was painfully obvious that he’d wasted $1,500 of his father’s money. His only shot at freedom was to get out of detention, delay his hearing and prepare his asylum case with legitimate legal assistance.

But why was he kept in detention for so long? As an asylum seeker, he’d exercised his right to request protection under international law. He’d already proven to an asylum officer that he had a well-founded fear of persecution, and he had no good reason to fail to appear at his court dates. But, regardless, the prospect of deportation loomed. Pakistan would mean violence or even death. What he needed was a sponsor, a helping hand that could lift him out of detention.

Eventually, a fellow detainee, an Arab man, told him there was a place where “some Christians” could maybe help him. The place was located in a city in Texas and it had a Spanish name, Casa Marianella, that he couldn’t quite pronounce. The man told Ghulam he should write to them and ask for their support.

In a letter, he scribbled out his life story and a plea for help. He doubted that anyone would ever read it. So far, America had given him little cause for hope.

Read the rest of Ghulam’s story in Part II of our series “America Beyond Detention.”

This article was ortiginally published in the Texas Observer.

Gus Bova, a Kansas-Texas transplant and inveterate protest-attender, is an editorial intern at the Observer. He can be contacted at bova@texasobserver.org.

This project has been made possible with the support of Solutions Journalism Network, a non-profit organization with the mission to spread the practice of solutions journalism.

[Photo by Jen Reel]