Can a Colonial Crafts Town Survive Modern Mexico?

*The crafts made and sold around Pátzcuaro, México, are traditions that date back to 600AD. There are deep traditions from across the continent and the Caribbean that establish the prominence Latino culture. Our children won’t get this version of history in public schools. This is up to us. VL

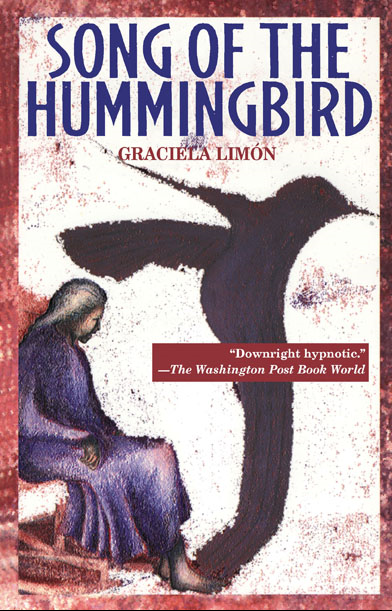

![]() By Laura Fraser, Craftmanship Magazine

By Laura Fraser, Craftmanship Magazine

On Friday mornings in the colonial town of Pátzcuaro, Mexico, there is a flea market where indigenous people barter their wares the way they’ve done since before the Spaniards set foot in this region. Squat, weathered women in long braids and woven rebozos carry baskets of dried fish, avocados, or wood scraps, which they trade for the used clothing, pots, or medicinal herbs that other natives have spread out on blankets.

The local crafts traded or sold around Pátzcuaro date back much earlier; copper-smithing, for one, has been traced to 600 AD. The native Tarascans, whose vast empire was seated in Pátzcuaro and nearby Tzintzuntzan, had the resources to develop a variety of sophisticated crafts, and the emperor surrounded himself with artisans who created textiles, arms, feather adornments, and copper and clay vessels. Clay was abundant in the hills around Pátzcuaro, which led to many different approaches to the ceramic arts. One reason the Tarascans were never conquered by their fierce Aztec enemies was their superior metallurgy. They were no match for the Spanish conquistadors, however, who arrived in 1522, plundered those treasures, and killed any Tarascans who stood in their way.

Click HERE to read the full story.

[Photos by Janet Jarman courtsy of Craftmanship]

Suggested reading