One way to decrease the drop-out rate in Chicago Public Schools

*According to Pew Research the Latino dropout rate has dropped to 14%. In the last 20 years the rate has declined from 33% in 1993 to where it now stands. This is good news, unless you’re one of the 14%. NewsTaco writer and Chicago high school teacher Ray Salazar has an idea for that. VL

By Ray Salazar, The White Rhino (6 minute read)

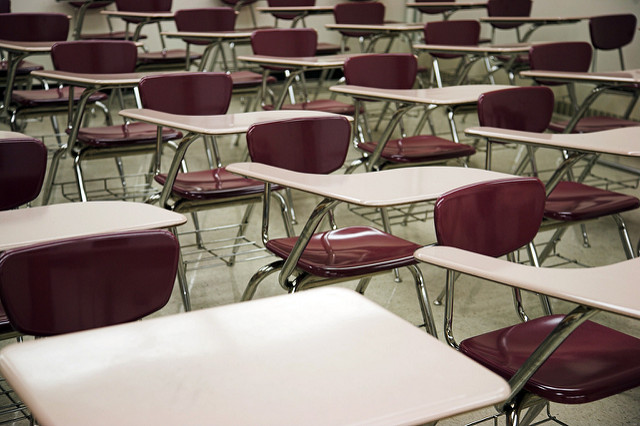

Today, Chicago Public Radio and the Better Government Association reported that Chicago Public Schools made significant adjustments to the high-school graduation numbers that senior leaders and Mayor Emanuel touted for years. To many of us teaching and working in CPS, this was no surprise. We know much of our work has become a numbers game. The data obsession pushes conversations about changing the data with little or no time to discuss the underlying factors producing the data.

If CPS leaders, school administrators, teachers, and staff spent less time obsessing over data points and instead focused on discussing underlying issues we can address reasonably, the data would improve by itself and we’d provide more meaningful learning opportunities to our students.

One key element that can drive data improvement is the quality of professional relationships in schools. As adults, we know that when we don’t feel valued or included or safe in our workplace we, if we have the option, usually look for another place of employment. It’s the same for high-school students.

We have a responsibility for making school a place where students feel like they belong. The strong and the damaged relationships in a school can be sensed by almost anyone who walks into a school building. Our human instinct helps us sense inclusivity; we can also sense tension.

READ MORE HERE

This article was originally published in The White Rhino.

[Photo by John/Flickr]

Suggested reading