A History of Latino Conservatism, Part 2: The Rise of Latino Neoliberalism

*If you’ve asked yourself how the GOP could engender two presidential candidates with Latino last names, the answer, according to Aaron Sanchez, is 100 years in the making – and it’s not an accident. Latino neoliberalism, he says, is a consequence of a Latino social and fiscal conservatism that goes back to the founding of LULAC and bolstered by the cold war and the Reagan administration. A very interesting read. I’d love to know what you think VL

![]() By AAron E. Sanchez, Commentary & Cuentos

By AAron E. Sanchez, Commentary & Cuentos

As covered in part I, Latino conservatism is not an outlier or a historical aberration. Many of its features developed over the course of the early twentieth century and were, at first, fused to civil right goals. Civil rights social conservatism accepted the idea that racial and economic inequality was not the product of structural problems, but individual failings. For these middle-class mid-20th century Latinos, Anglos did not systematically exclude Latinos, nor did they make Latinos poor. Instead, Latinos kept themselves in poor economic conditions and in segregated neighborhoods because they refused to assimilate, learn English, become educated, and be industrious with their time and money. Groups like LULAC and the American GI Forum subscribed to these types of ideas for much of their histories.

Latinos were not immune to the powerful social forces of the Cold War. The political standoff between the U.S. and the Soviet Union quickly became a contest between two antithetical ways of life. Both could not coexist. The need to define the American way of life created a culture of conformity that rested on certain key components: the nuclear family, heteronormativity, consumption, and capitalism. The nuclear family in the 1950s was not “traditional” or long established. It was the nuclear age that ushered in the American nuclear family. The Second Industrial Revolution, the Great Depression, and two world wars had challenged and changed familial roles and patterns for much of the twentieth century. But in the post-WWII economy, a time when many believed that the problem of scarcity had been solved, the nuclear family seemed a way to actually prove American economic and cultural superiority in the world. So productive and superior was the American economy that women did not need to work, nor did children have to worry about their next meal. It was believed that the nuclear family provided stability and a model of how the world should work—responsible men would work, made decisions, and provide for their dependents. Since families were so important to proving the superiority of the American way of life, heteronormativity was also elevated in importance. In fact, heteronormativity was central to national security: America needed soldiers to fight the communists; families provided young boys who would become soldiers. Only men and women could procreate and only strong families could provide those young-would-be-soldiers the necessary moral upbringing to maintain peace and goodness in the world. Since these men would have to fight a world war if it came to that, they needed to be strong, masculine, and virile; they could not be sissies. Because of these retrograde and discriminatory stereotypes, homosexual men were targeted as potential physical liabilities and possible communist spies. Many middle-class Mexican-Americans, especially recent WWII veterans, agreed with this brand of social conservatism. They believed in the male privilege which much of Cold War culture was built upon.

In 1959, the Cuban Revolution came to a close as Fidel Castro and Che Guevara arrived victoriously in the capital city of Havana. Very soon afterwards, waves of Cuban exiles poured into southern Florida. The first arrivals were wealthy and middle-class Cubans who were fleeing Castro’s redistributive policies. Nearly 40 percent of this group that came between 1959 and 1963 had college degrees at a time when only 4 percent of the general Cuban population had a high school diploma. As ardent anti-communists and devout Catholics, Cuban exiles bolstered Latino social conservatism in the mid-20th century. They helped give Latino social conservatism more political power as they gained clout in south Florida.

It was the long decade of the ‘60s that delinked social conservatism from civil rights struggles. Latino civil rights social conservatism explained the causes of racial and economic inequality as the consequence of the behaviors and actions of the minority communities themselves and not racism or the failures of capitalism. Across the nation, groups like MEChA, the Young Lords, and the Black Panthers believed there were structural flaws in American society. Moreover, it was American capitalism that created and perpetuated racial and economic inequality. This irritated civil rights social conservatives who had believed for nearly half a century that it was the Latino community’s own ineptitude or its own sloth that hindered them from success. Capitalist competition provided the Latino community an avenue to compete with, and beat, their Anglo peers, proving their equality. Success in business for Latino social conservatives proved that they were just as smart, talented, and capable as whites. Their bank accounts were objective measures to prove their equality.

On top of this, the calls for self-determination, sexual liberation, gender equality, and decolonization coming from youths terrified the older and middle-aged Latinos. They saw sexual liberation as moral depravity. Self-determination, an admittedly ambiguous concept, sounded like communist-tinged anti-Americanism. The young generation of Latinos coming into political consciousness took aim at the very tenets and structures that gave life meaning to the prior cohort. LULAC member Jacob Rodriguez illustrated the irritability of the older generation with Chicanos in a multi-page essay complaining about Chicanas and Chicanos. He wrote in the late 1960s, “The term ‘Chicano’ was, and is, an insult, no matter how it is used…[it is] intended only to apply to the Mexican wetback. Is that what you are? It can’t even be dignified ‘kitchen-Spanish’ since all it is, is ‘gutter-Spanish.’” Rodriguez argued that the term Chicano had its origins that connected it to the word “pigsty.” He then went on to illustrate the condescension of social conservatives toward Chicanos:

The younger generation doesn’t know any better. It still has a lot to learn….Our youngsters’ lack of living, practical experience and comprehension is impelling them to ‘identify’ with something and—unfortunately for them and all the rest of us—they don’t even know what with or why. All they feel is that this word is a call to rebellion…Imagine burning your own Flag for something like that, and hoisting a foreign, alien, flag in its place! Only the years will teach them better!

In 1978, Mexican-American academic and professor at the University of Montana, Manuel A. Machado, wrote a neoconservative history of Mexican-Americans that made fun of and belittled Chicano ideas and scholars titled Listen Chicano! Barry Goldwater wrote the forward. The generational divisions between older and younger activists were showing.

It was Richard Nixon in his bid to win re-election that first tried to carry out a political agenda that would appeal to both racially anxious lower middle-class whites and Latinos. Nixon developed the “Southern strategy” that used racial code words to win over white voters. At the same time, after creating a broad term to link the various Spanish-surnamed and Spanish-speaking groups in the country, he courted Hispanics with his “Hispanic Strategy.” He won 35% of the Hispanic vote in 1972 (a mark that most Republicans would aspire to today). By 1974, Republican National Committee chairman George H.W. Bush formed the Republican National Hispanic Assembly.

While Nixon was the first Republican to court Hispanics in a presidential campaign, Hispanic Republicanism had already started to take shape in Texas by the 1960s. Latino social conservatives felt pushed out of the civil rights arena by younger, more progressive activists. Increasingly, they sought political representation in, what was then, a single-party state. The Democratic Party had been in power in Texas since Reconstruction. Yet, a political shift was underway, as LBJ, a Texan Democrat, had signed civil rights legislation that most Southerners disagreed with in the 1960s. Republicans in Texas made their case for election on the grounds that they were the truer and more authentic conservatives. In 1966, John Tower received 30% of the Mexican-American vote to become one of the two Senators from Texas. There was not another Republican in the entire state that received more than 8% of the Mexican-American vote at that time. Tower was also the first Republican to speak at the LULAC national convention, an important national organization that was founded in Corpus Christi, Texas in 1929. From then on, Hispanic Republicanism was courted and groomed in Texas.

By the mid-1970s, the transformation of the American economy from an industrial-manufacturing economy to a postindustrial service oriented economy was underway. The drastic changes of the American economy had dramatic social consequences. After nearly a decade of social change, many white Americans believed that increased minority political participation led to their own economic decline. Many middle-aged Latino social conservatives also believed that it was the youths’ angry rhetoric and communist ideas that undermined American greatness. Deindustrialization caused high unemployment and economic recession. Neither Republican nor Democratic presidents could fix the economic problems of the ‘70s. It seemed for many Americans and politicians that the statist programs and policies that had been so popular since the New Deal no longer worked. Mindful and managed government cooperation with private industry could not solve the recession. If statist programs were not the solution, then what was? It was in downfall of the liberal consensus that Neoliberalism came roaring back, with Latinos in its crosshairs.

As faith in government withered, because of Vietnam, Watergate, and the seemingly unending recession, Americans began to believe that government could not solve the country’s problems. In the now infamous 1979 “Crisis of Confidence” speech, Democratic president Jimmy Carter seemed to admit as much about the economic and social stagnation and perceived decline of the United States. He explained that all the problems facing the country—recession, inflation, unemployment, loss of optimism—were symptoms of a bigger, worrisome disease, “symptoms of this crisis of the American spirit.” This was a crisis that the government could not solve, for it was a crisis of confidence. It was a crisis of American character, values, and faith. These could only be addressed by individual and personal contemplation. The government could legislate, but it could not soul-search. There were limitations to what the government could do, liberals finally admitted.

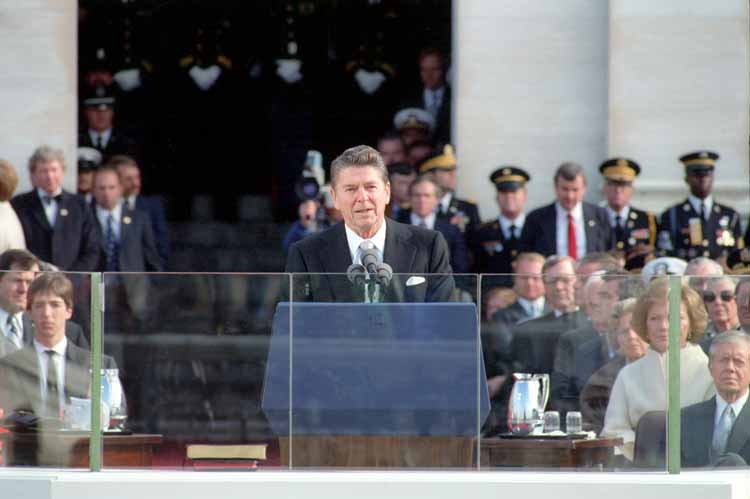

With the ideological concessions of liberals and the changing political calculus of the nation, Ronald Reagan pushed conservatism to a new level and revived ideas about the economy and poverty that had lost most of their credibility with the Great Depression. Instead of national reflection and idle rumination, he offered answers and direct explanations. In his 1981 inauguration, he revealed the true culprit of American decline: “in this present crisis” he began “government is not the solution to our problems; government is the problem.” Regan garnered 33% of the Latino vote in 1980 and would increase that percentage to 37% in 1984. Interestingly, he carried the heavily Mexican-American Cameron and El Paso counties in Texas.

The Reagan Revolution redefined the engine of social change in the nation and the world. No longer was government a force for change and social good; it was a corrupt, inefficient, overgrown, over-reaching leviathan. The social metaphors that bound the nation together changed as well. No longer were Americans bound together by mutual obligation—things like paying taxes, supporting social programs for the less fortunate, attending integrated public schools—that would maintain national unity. Instead, of unifying social metaphors, Reagan offered the disaggregation of society into private individuals. The proper mechanism for change was the market, because it was in the market that individual, consenting, voluntary actors competed to produce the best outcomes. These outcomes could be objectively measured, of course, in dollar amounts, in the form of profit. The dawn of the neoliberal era ousted government from its key role in economic fairness and social change. Instead, the self-governing, voluntary, efficient, and profit/resource-maximizing market would shape society. The Reagan administration brought to a national level the idea that a radically individualized society would provide the best social outcomes. This had to do with the fact that neoliberals believed that individual competition provided objective proof of individual, corporate, national, or global success.

The ideas promoted by Reagan and other neoliberals resonated with Latino social conservatives. For decades, they had believed that poverty or success were individual ventures. For them, capitalist competition was the best way to prove to other groups that Latinos were equal to whites. Individual success was the best way for the community to achieve social success. Latino social conservatives were not necessarily interested in collective responses or collective social ascendancy—they were primarily interested in individual success. Once enough Latino individuals succeeded, then added up together, the community would be successful. Some influential Latinos took their place in the Reagan Revolution.

In 1991, Linda Chávez, a Reagan appointee, outlined a vision of Latino conservatism in her book Out of the Barrio: Toward a New Politics of Hispanic Assimilation. She agreed with Reagan, but added that not only was big government a problem, but it created the problems of Mexican-American racial and economic inequality itself. She lambasted Chicana and Chicano activists as anti-American, delusional separatists. She blamed the civil rights era and the civil rights legislation of the mid-1960s for creating government entitlements that caused Mexican-Americans to become dependent on the government. She wrote:

So long as Hispanics remained a separate and disadvantaged group, they were entitled to affirmative action programs, compensatory education, government set-asides, and myriad other programs. Previous immigrants had been eager to become ‘American,’ to learn the language, to fit in. But the entitlements of the civil rights era encouraged Hispanics to maintain their language and culture, their separate identity, in returns for the rewards of being members of an officially recognized minority group. Assimilation gave way to affirmative action.

Chicanas and Chicanos in the ‘60s and ‘70s argued that poverty was perpetuated by structural failures. Most social conservatives rejected this idea, but in the ideological transformation of the late 20th century they agreed. The difference, however, was that it was not capitalism that created and perpetuated poverty, but government dependency. The Latino community, Chávez and other Latino conservatives explained were intentionally kept poor by government officials eager to give them handouts instead of giving them the ability to be set free through the free market system. Chávez, blamed everything from bilingual education to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 for late twentieth century inequality. If not for these malevolent programs, the market and economic growth would have naturally elevated Latino or Hispanic, in her language, communities if government programs had not weighed them down.

The Republican return to power ended in 1992 with the election of Bill Clinton. However, this was not a political sea change. Instead, Clinton was a liberal neoliberal. Clinton did not believe that government intervention was required to ensure a secure position for every citizen in a fair economic system. Instead, he focused on free trade, welfare reform, and higher education. The 1994 NAFTA agreement did not challenge the idea that unregulated capitalism produced the best economic and social outcomes— it promoted the idea. NAFTA destroyed poor Mexicans economic security and made it easier for companies to move their factories to Mexican border cities, reducing American economic security too. In a global market with no protections and nothing but their labor to sell on the free market, Mexican migrants sought the highest wages they could. Of course, those wages were in the U.S., not in Mexico. While NAFTA promised to make goods and capital mobile, it did not promise the free movement of people. Instead, Clinton made migration more dangerous and difficult with his Operation Gatekeeper and Operation Hold the Line initiatives. These programs militarized and policed urban entry points, pushing unauthorized migration into the Sonoran desert. Migrants died daily crossing the desert between Sonora and Arizona. Clinton’s welfare reform only pushed people off of the roles, but did not address the very different economy that had emerged with the dot com bubble. Poor and working-class people continued to suffer through the ‘90s. His belief in higher education as a remedy to poverty did not address the structural inequalities of public and higher education either. Even with eight years of a Democratic presidency, conservative economic ideas continued to impact the Latino community.

By 2000, George W. Bush, then governor of Texas, was busy forging a “compassionate conservatism.” Bush benefitted from a growing Hispanic Republicanism in Texas and he also courted Latino voters early in his political career. In 1994, he helped steer the party away from anti-immigrant and anti-Latino policies like Prop 187 in Texas. Because of his relatively moderate immigration stance, his laughable Spanish, and his close connections to Mexican politicians, he garnered 49% of the Latino vote in his 1998 gubernatorial election. He used his familiarity with Mexican-Americans in Texas to engage Latinos across the nation in the run up to the 2000 election. In that election, he would win 35% of the Latino vote. His investment paid off and in the 2004 election Bush received 44% of the Latino vote.

Within Bush’s compassionate conservatism, Leslie Sánchez, a Bush appointee, fashioned a vision of a new Latino Republicanism in her 2007 book Los Republicanos. Still drawing back to Reagan, Sánchez maintained a hardline neoliberal economic outlook, but packaged it in a kinder, informal writing style. She called liberalism a policy of “empty promises” She described Democrats and liberals as whiners and victims. Republicans, on the other hand, were “optimistic” and “spoke about family faith, honor, love of country, and hard work.” “[Republicans] bore a sense of national purpose” she added, “They inspired my hopes about creating opportunities….By standing firm and by taking personal responsibility, [Republicans] could achieve so much more…”

Nonetheless, she opposed the nativist, anti-immigrant rhetoric that had become popular in her party. She refused to write-off the Latino community as immigrants, foreigners, and parasites. Instead she argued that “Latinos will listen [to Republicans], as long as there’s someone who wants to talk to us.” She pointed out, sadly, that most Republicans only speak about Latinos in a negative, paranoid, stereotypical way, calling out Tom Tancredo of California in particular. She hinted in 2007 that this kind of language had the ability to make Republicans a permanent minority, with a small and shrinking base.

Although Sánchez wrote in a less polemical style as Linda Chávez, the two agree that government dependency is the biggest problem the Latino community faces. “Latinos must ask themselves, “Sanchez writes “if they want a share in the empty [Democratic] promises that have so failed black America.” She asks in an exaggerated fashion if Latinos want to “become a new victim class for the benefit of the American left.” She draws upon supply-side or trickle-down economics to support her assertion that Republicanism is a natural fit for Latinos: “No tax hike or wild-eyed feminist rant has ever helped a single immigrant family succeed in this country. Republicans can draw Hispanics in America away from the siren song of government dependency—if only they are smart enough to welcome their neighbors.”

In the post-Regan decades, Latino conservatism has increasingly tried to assert that neoliberal ideology is most closely related to Latino values. In 2011, the Libre Initiative was founded in South Texas, funded by the Koch brothers. According to its website, the Libre Initiative:

advances the principles and values of economic freedom to empower the U.S. Hispanic community so it can thrive and contribute to a more prosperous America. LIBRE is dedicated to informing the U.S. Hispanic community about the benefits of a constitutionally limited government, property rights, rule of law, sound money supply and free enterprise through a variety of community events, research and policy initiatives that protect our economic freedom. Our mission is to equip the Hispanic community with the tools they need to be prosperous. We are committed to developing a network of Hispanic pro-liberty activists across the United States so that our message reaches every corner of the country.

The Libre Initiative pushes the notion that neoliberal libertarian values are the truest and most authentic Hispanic values. They build upon the legitimate concerns that many immigrant Latinos have about authoritarian states. Many Latin American immigrants have experiences with corruption, unfair taxation, and participation in the informal economy in their home countries. Libre tries to equate these problems with limited “economic freedom.” That is, the problems faced by Latino immigrants and their home nations are that the market has been overregulated and restrained. If only those nations and politicians deregulated, de-taxed, and down-sized their bureaucracy, the immigrants themselves and their nations would be successful. Libre warns that this is what is happening in the U.S. They warn that Democrats only want to turn the U.S. into a dictatorship. Only the unchecked, unregulated, free-market can promise individual freedom.

What the Libre Initiative fails to mention is that Latin Americans from Central and South America primarily fled right-wing governments that conservative American presidents supported. In addition, American policies that promoted globalization and the removal of worker protections negatively impacted the poorest across the globe. It was not American liberalism or progressivism that failed Latin Americans, but neoliberal agendas. Since the 1970s, international agencies like the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank have forced developing nations to reduce protections and taxes to the detriment of their own fiscal and national interest. These tax cuts, corruption, and drug wars have caused many states to fail. It is failed states, not statist liberalism that caused the problems for Latino immigrants.

In 1984, Lionel Sosa, a Hispanic Advisor to Ronald Reagan, told the president “Hispanics are already Republican. They just don’t know it yet.” Since the Reagan Revolution, Latino conservatives have tried to convince the Latino community that their values and beliefs are really Republican policies. Latino conservatives have successfully built upon the social conservatism of the mid-20th century, after it was unhitched from civil rights activism. Most recently, they have adjusted the message of Republican neoliberalism. The idea that poverty is the product of an individual’s own personal moral failings has been turned into: Latinos work harder than everybody else. They have used the concept of familial pride to shame people who need government assistance: those who need help are lazy sin verguenzas. They have toned-down the ideologically ingrained cultural deficiency theories of conservatism into: Latino success depends upon speaking English and assimilating. And perhaps most importantly they have promoted the dominant trope of neoliberalism: dependency. Dependency is a concept borrowed from the 18th and 19th century that warned that economic dependents could not be trusted with the responsibility of electing their own leaders because they could be manipulated by their employers or creditors. In its 20th and 21st century iteration, dependency is the debased condition of perpetual indebtedness to the government. Latino conservatives believe that government is the problem and the government creates the problems itself. The protections that generations of American workers fought to receive have been turned into selfish “entitlements” by Latino conservatives. The government then, they explain, uses these entitlements to maintain dependency on the government, perpetuate poverty, and keep Latinos isolated and segregated. Only the free-market can truly set Latino free. Latino conservatism in the second half of the twentieth century was informed by and helped transform mainstream American conservatism.

It should be no surprise then that the Republican Party is the first to put forward the first Latino presidential candidates, Raphael “Ted” Cruz and Marco Rubio. Cruz and Rubio are not anomalies. They are products of a long history of Latino conservatism, nearly a century in the making.

This artilce was originally published in Commentary & Cuentos.

[John Tower, Ronald Reagan, Linda Chavez, and Leslie Sanchez photos via Wikimedia]