How I Earned My Citizenship Defending This Country

*This essay is one of a series of personal accounts compiled by CUNY Graduate School of Journalism student Rachel Glickhouse. The series is titled “My Time in Line,” in which immigrants write about their personal experiences about the mythical “line” to get legal status. There’s a misconception in the immigration debate that people can simply “go to the back of the line,” but there’s little understanding that there is no real line, and the process is long and difficult. These essays serve to dispel that idea. We’ll be posting more in the days to come. Share them with whomever you think needs truth. VL

By Fernando Sacoto, Medium

By Fernando Sacoto, Medium

This is the story of how I went from an undocumented immigrant to a U.S. citizen in a single day — after fighting for the country I’ve called home for more than 25 years.

I was born in Ecuador in 1967, the tenth of 11 siblings. My father was a farmer, and my mother was a housewife. After high school, I wanted to be a pilot in the Ecuadorian air force, but the vision test disqualified me. I joined the army instead, completing one year of mandatory training. I hoped to become an officer, but I was discharged because I was two inches too short. I got a job as a cleaner at a hotel and for eight months, I worked 100 hours a week, making $34 a month.

At that time, everyone was immigrating to the U.S. I realized I could, too, help my family and have a better future. I left Ecuador without a visa on September 13, 1988.

I traveled from Ecuador to Colombia, from Colombia to Panama, from Panama to Guatemala, and from Guatemala to Mexico. The coyotes, or smugglers, threatened to take us to the authorities, forcing us to give them more money. At one point, two of my friends and I decided to break off from the group and make the dangerous journey over the U.S.-Mexico border. Hiding from helicopters and searchlights, walking more than four hours guided by the smugglers, we finally made it to a car waiting for us in San Isidro, California.

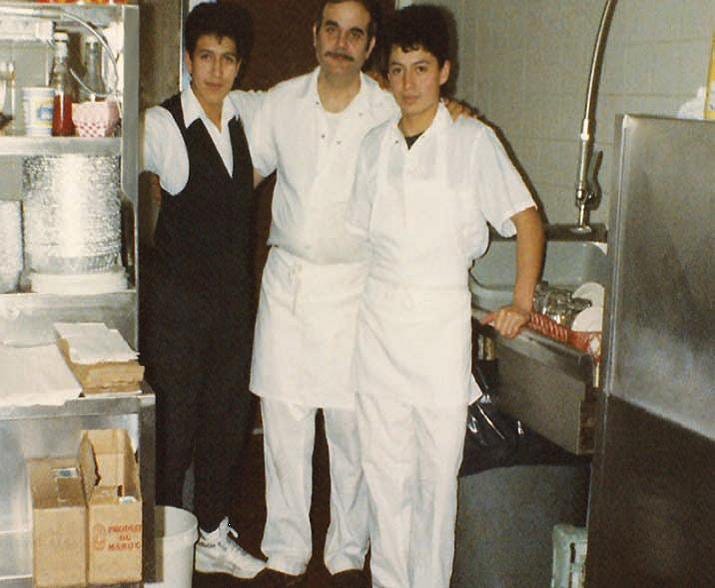

I woke up in the trunk of the car in a hot parking lot in Los Angeles. I went to live with a friend in New Jersey and got work at a restaurant preparing food, and later as a busboy. The hardest part was trying to learn English. I badly wanted to go back to Ecuador, but I had to repay the money that my father had borrowed. If I didn’t, he would lose the property he used as collateral.

My English improved, and I was promoted to waiter. To continue working, I realized I had to get a driver’s license. So in 1989, I began an odyssey to try to become a legal resident.

First I went to a lawyer in Long Island City, New York and paid $1,800 with the assurance that if I gave them my passport, I would receive legal residency. I received some paperwork, but when I called the lawyer’s office to check on my application, the number had been disconnected. Later, another man charged me more than $5,000 for a similar guarantee, and I was cheated again — with no progress towards citizenship. Around this time, I had two interviews with immigration and the second “lawyer” gave me my passport with a fake residency stamp.

One day, I stopped by a U.S. Army recruiting office. I showed the recruiting officer my Ecuadorian passport with that stamp to enlist, and all that was left was to verify my immigration status. For reasons I can’t explain, he never followed up. I signed up for a five-year enlistment a few weeks later.

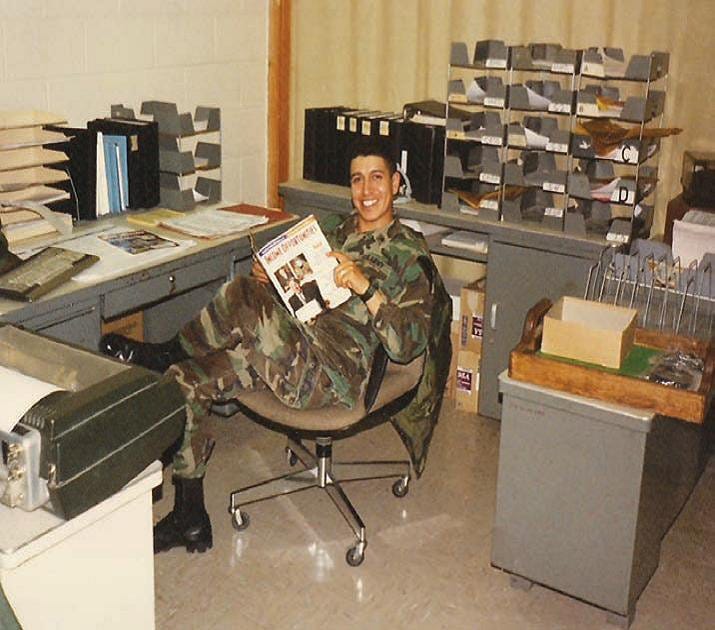

A few weeks into basic training, I learned that my latest attempt to legalize my status was fraudulent. Since I was in the Army already, I stayed quiet. I was very proud to serve in the best army of the world, ready to defend the country that gave me the opportunity to have a better life. After graduating from Advanced Individual Training in May 1991, I finished fifth in my class and made the Commandant’s honor list.

My first permanent duty station was in Nuremberg, Germany. With my military status I was given the opportunity to travel and to live as a free person rather than an undocumented immigrant worrying about my status. I was able to feel protected and secure from being detained and deported.

In Germany, I provided administrative support to the troops coming back from Kuwait, serving as a link between the families and the soldiers. After two years, I was reassigned to Panama to the 308th Military Intelligence Battalion. Another two years later, I was stationed in Fort Hood, Texas, in a cavalry unit. During my time in the military, I received 3 Army Commendation Medals, 3 Army Achievement Medals, and 3 coins.

Serving in the military allowed me the freedom to start a family. I traveled to Ecuador using my army ID and married my high school girlfriend before returning to Germany. When reassigned to Panama, I went to Ecuador to meet my daughter for the first time. She was six months old.

After my five-year enlistment, I talked to a military lawyer who told me that due to my immigration status, it would be better not to re-enlist. This was my biggest disappointment, since I always wanted to make a career in the military. When I left the army, I felt sad and lost. I had to start living life again as an undocumented immigrant.

After my honorable discharge in 1996, I transferred to the New Jersey National Guard for a year and a half. I then returned to New York, working in various restaurants for three years and then as a carpenter’s apprentice. Twelve years ago, my brother and I opened a contractor and home improvement business.

Since we started, we worked on over 600 houses. My struggles and accomplishments allowed me to provide my family with a home, food, clothing, and most importantly, the opportunity to get an education. Already, my eldest daughter graduated from Rutgers University with a double major in biology and criminal justice.

In 2003, I learned that because of my military service occurred during a “period of hostility,” I qualified to become a U.S. citizen, regardless of my status. This time; I talked to a lawyer from Catholic Charities to help me with the process.

On April 17, 2006, I changed my status from undocumented to a U.S. citizen in a single day after 17 years in this country.

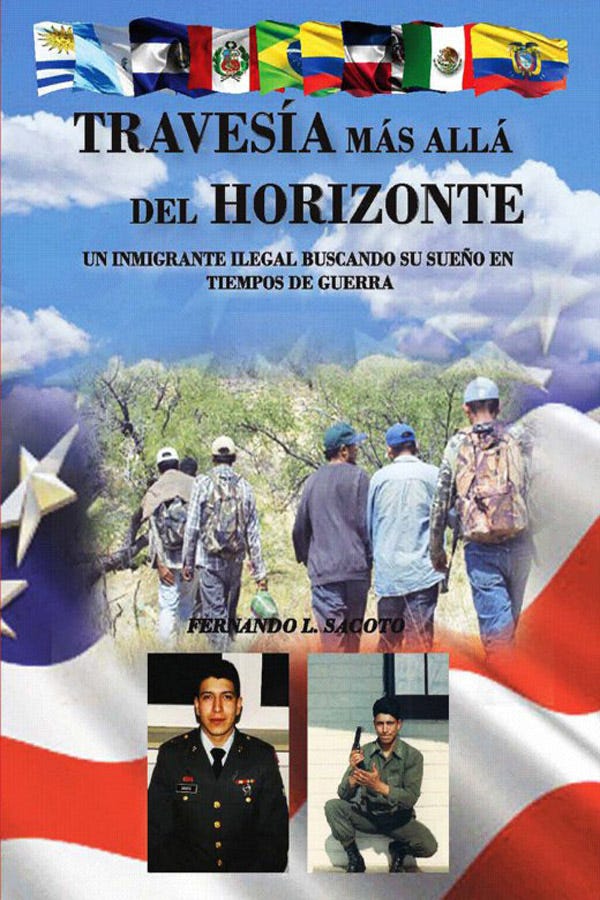

Since I became a citizen, I was able to get my driver’s license, making life a lot easier and improving my business. I could vote and express myself politically. I could visit my parent’s graves, since they died when I was undocumented and couldn’t travel to Ecuador for their funerals. In 2010, I wrote a Spanish-language autobiography about my odyssey called “Travesía Más Allá Del Horizonte” (My Journey Beyond The Horizon). The truth is that I considered myself an American the day I enlisted in the army, and was willing to make the ultimate sacrifice for this country.

This essay was edited and adapted from a previous essay I wrote for the Define American blog.

This article was originally published in Medium.

[Photos courtesy of Fernando Sacoto]