10-Year-Old Gets Mission Song Stricken from California School District Curriculum

*I post this for context. We’ve been having an interesting conversation about the role of Father Junipero Serra and the colonization of California. Serra will be canonized by Pope Francis, but his statue will be removed from Statuary Hall in Washington. Serra is a controversial figure, and among Native Americans he is vilified for his role in subjugating the indigenous people. This story, about a 10 year-old Native boy and a song he refused to sing in school, follows many of the ideas central to the Serra discussion. VL

By Alysa Landry, Indian Country/New America Media

By Alysa Landry, Indian Country/New America Media

A 10-year-old Wukchumni boy is changing the way one California school district teaches Native history.

Alex Fierro, a fourth-grader in the Visalia Unified School District, was uncomfortable with a song he was learning in the music program. The song, called “Twenty-One Missions,” references a difficult chapter in the history of California’s coast.

The Spanish missions in California, established by Catholic priests of the Franciscan order between 1768 and 1833, were part of the first major effort to colonize and Christianize the Pacific Coast. The missions, 21 of them built in a chain along the coast, were founded to convert, educate and civilize the indigenous people—usually by enslaving them and using them for labor.

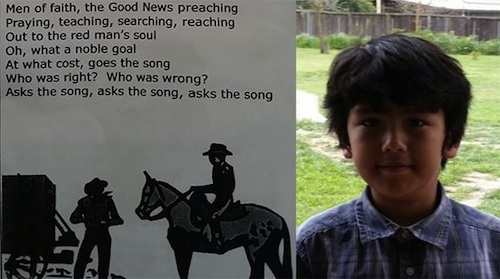

The song, written in a minor key, calls attention to the missions, which were “made of earthen brick” with “massive walls, three feet thick.” The lyrics also explore the purpose of the missions: “To save the soul, soothe the savage breast.”

When he first heard the lyrics, Alex decided not to sing them. Eventually, he told his mom that they made him uncomfortable.

“When I heard the lyrics of the song, I didn’t really like them,” Alex told ICTMN. “I thought it was offensive.”

Alex took a copy of the lyrics home and his mom, Debra Fierro, wrote a letter to Alex’s teacher, principal and district administrators.

“I tried to get Alex to sing part of the song, but he wouldn’t do it,” she said. “He didn’t even want to say the words out loud. So he brought home the lyrics, and I just got this pit in my stomach. I felt horrible.”

Fierro also alerted Darlene Franco, chairwoman of the Wukchumni Tribe, who wrote a letter of her own to administrators, asking that the district do four things: remove the song from its list of approved materials, provide information about the origin of the song, introduce cultural sensitivity training for teachers, and apologize to Alex.

The missions almost wiped out the Wukchumni, Franco said. The tribe was located in central California, and the missions relocated the people to the coast.

“As a result, there was a lot of death,” Franco said. “It was another genocide. It was enslavement, mistreatment. It was 10 times worse than boarding schools, and as a result, most of the Native people on the coast are not federally recognized.”

The song, Franco said, was part of the curriculum for fourth-grade California history. It told the story of the missions from the Catholic perspective, but failed to capture the full impact on the Natives.

Franco also found the lyrics offensive, particularly the “noble goal” of “praying, teaching, searching, reaching out to the red man’s soul.”

“It’s all a part of the white fathers looking down on the Indians,” she said.

District officials jumped into action, responding to Fierro’s letter the day after she sent it, Assistant Superintendent Doug Bartsch said. Within a week, the song had been pulled from the curriculum and Alex received an apology.

The district also took a hard look at the song and how it was being used to teach California history, Bartsch said. A California singing group praised for its historically accurate lyrics wrote the song in the year 2000. In fact, the song ends with these poignant questions: At what cost? Who was right? Who was wrong?

“It’s a melancholy song, written in a minor key,” Bartsch said. “It’s meant to be a sad song. So maybe the intentions were noble, but there was a cost to writing this song. This song was intended to show the complex history of this time, but we can’t guarantee 9-year-olds or 10-year-olds get all that.”

About 28,500 students go to school in Visalia. Eight hundred of them are Native, or about 2.8 percent of the total student population.

Fierro described Alex, the youngest of her three children, as “very intellectual.”

“He always wants to know why,” she said. “He’s always listening. In his 10-year-old mind, he knew he didn’t like the song. We keep telling him he’s a catalyst for change, but I don’t think he quite knows what to make of that.”

The incident has already generated change, Bartsch said.

“This process has stretched my own perspective,” he said. “I like to think of myself as culturally sensitive, but we all miss stuff. We want to continue working with local tribes, to get together and listen more, to think about what we can do better in the future.”

This article was originally published in Indian Country and New America Media.

Alysa Landry is a professional journalist based in the Four Corners area, she writes mainly about the Navajo Nation, the largest tribe in the country.

[Photo courtesy of New America Media]