Remembering a Modest Cesar Chavez

*Anita Quintanilla was Cesar Chavez’s first female bodyguard, a fact I learned through a Facebook exchange during the recent days of the premiere of the Chavez bio-pic. Two things stand out: one is the humanity of the man who has been elevated to an iconic level, and the other is the wonderful community of Taquistas that continues to surprise me – especially when they agree to share their stories. Personal, heartfelt, this is a special read. VL

By Anita Quintanilla, NewsTaco

While working with Dolores Huerta in the mid-70s in New York City I was able to observe Cesar’s humanness. He spoke at different events, including one occasion with the Kennedys and Shrivers and other influential people in Boston. Cesar’s humanity and sincerity seemed to dissipate any arrogance that may have been lingering in the air. In California in January of 1977, while taking a break from organizing farm workers with Arturo Rodriguez, I stopped off in La Paz, the UFW headquarters. While there Cesar approached me and asked if I wanted to be one of his security guards. He felt it was time to have a full-time female guard. At first the head of the security department assigned me to just office work until Cesar got mad at him and insisted that I also go on the road with them.

On one of these trips I remember we stopped to eat in a park in Sacramento and Cesar told us about a time he went to a huge social event of politicians and celebrities in Mexico City. The hosts of the event offered him female companionship. Cesar was shocked and the hosts were embarrassed and apologized. In retelling this incident Cesar’s face was very expressive in showing his reaction and theirs. On these road trips I usually rode in the “suicide car” but one time I occupied the station wagon with Cesar and the driver. As we drove through the central valley of California, Cesar would tell us the UFW history of each town. It was such a pleasure and comfort to hear his soothing voice and such an honor to be privy to his recollections and reflections. He sure loved talking! During another trip we all stayed at his cousin’s house in Phoenix, Arizona. Early the next morning I had to go into the bedroom to tell Cesar that it was time for him to wake up. I felt bad about having to disturb his sleep, knowing how much he needed rest. I’ll never forget his sleepy face lifting up from the pillow and turning towards my voice.

On one of these trips I remember we stopped to eat in a park in Sacramento and Cesar told us about a time he went to a huge social event of politicians and celebrities in Mexico City. The hosts of the event offered him female companionship. Cesar was shocked and the hosts were embarrassed and apologized. In retelling this incident Cesar’s face was very expressive in showing his reaction and theirs. On these road trips I usually rode in the “suicide car” but one time I occupied the station wagon with Cesar and the driver. As we drove through the central valley of California, Cesar would tell us the UFW history of each town. It was such a pleasure and comfort to hear his soothing voice and such an honor to be privy to his recollections and reflections. He sure loved talking! During another trip we all stayed at his cousin’s house in Phoenix, Arizona. Early the next morning I had to go into the bedroom to tell Cesar that it was time for him to wake up. I felt bad about having to disturb his sleep, knowing how much he needed rest. I’ll never forget his sleepy face lifting up from the pillow and turning towards my voice.

At La Paz, located high in the Tehachapi Mountains, Cesar was able to relax a little with the community and his family. He liked to joke around and playfully tease others. At a small ceremony for union organizers, Cesar tried to pin a UFW button on my jacket, which was already covered with several buttons. He jokingly asked if I had enough buttons. One day while we were all gathered outside the community kitchen Cesar took advantage of this opportunity to indulge in his passion for amateur photography. He would say silly things to make us smile for the camera, which he held right up to our faces. One morning Cesar wanted to celebrate the birthday of Dolores’ oldest daughter Lori. He managed to convince some of us to get up very early to sing “Las Mananitas” to her after he served us hot Mexican chocolate with Tequila in it! He went around with a quizzical expression on his face, offering us more to drink. This was one of his less serious ways of celebrating his Mexican heritage. At several social occasions we had there at La Paz, Cesar had opportunities to pursue his love of dancing, which he was very good at. One day some of us joined Cesar in the community garden. As his small dark fingers sank into the warm soil he patiently described to us the many different kinds of chilies there were. I was amazed by the wealth of knowledge he had about plants and the environment.

In one conversation we had together I told Cesar about how successful we Chicanos at U.T. were at eliminating non-UFW lettuce on the campus and how we had staged a sit-in in the Governor’s office, requesting that day be proclaimed “Cesar Chavez” day. Cesar responded by telling me how students were such a powerful base of support and how their dedication and commitment helped the Union accomplish its goals. This man, who I loved like a father, taught us some hard lessons about being responsible for our actions — that “the buck stops with me.” If we messed up he wanted to hear us say, “Yes, I f—ed up.” Of course, he also emphasized the importance of learning from our mistakes. Possibly the last time I saw Cesar was in 1985 while I was helping at Teatro Campesino’s 20th Anniversary celebration in San Francisco. As his hostess, I checked with Cesar to see if he needed anything, and, not liking to be pampered, he quickly and politely responded that he was just fine. I was glad to see him enjoying himself at this gala event. Years later when I heard that Cesar died I was sad but also not surprised. I just knew that with his intense drive for justice he would never ease up on his fight against California’s corrupt agribusiness. The 40-year war they waged with the growers (with the help of the John Birch Society, the FBI, Teamsters, Republicans and police) finally took its toll on this non-violent warrior.

In one conversation we had together I told Cesar about how successful we Chicanos at U.T. were at eliminating non-UFW lettuce on the campus and how we had staged a sit-in in the Governor’s office, requesting that day be proclaimed “Cesar Chavez” day. Cesar responded by telling me how students were such a powerful base of support and how their dedication and commitment helped the Union accomplish its goals. This man, who I loved like a father, taught us some hard lessons about being responsible for our actions — that “the buck stops with me.” If we messed up he wanted to hear us say, “Yes, I f—ed up.” Of course, he also emphasized the importance of learning from our mistakes. Possibly the last time I saw Cesar was in 1985 while I was helping at Teatro Campesino’s 20th Anniversary celebration in San Francisco. As his hostess, I checked with Cesar to see if he needed anything, and, not liking to be pampered, he quickly and politely responded that he was just fine. I was glad to see him enjoying himself at this gala event. Years later when I heard that Cesar died I was sad but also not surprised. I just knew that with his intense drive for justice he would never ease up on his fight against California’s corrupt agribusiness. The 40-year war they waged with the growers (with the help of the John Birch Society, the FBI, Teamsters, Republicans and police) finally took its toll on this non-violent warrior.

The movie Cesar Chavez, directed by Diego Luna, which was only 100 minutes long, was unable to create a full picture of the man beyond a heroic leader. Cesar was an ordinary man and it was his upbringing and life experiences that built his character and social consciousness. Chicanos and liberals had built Cesar up to be a larger-than-life leader, a man of, for, and by the people. He was the answer to their and society’s problems and everyone demanded and expected more of him. He was considered a saint, a national labor leader, a Chicano icon, an American Gandhi, a Mexican Martin Luther King, Jr., etc. Cesar was only human and made mistakes, but throughout the years he learned more and evolved into a better person. He certainly wasn’t the same person who used the word “wetback” in an interview in the 1960s. If he was alive today there is no doubt that he would be involved with immigration reform that would help migrant workers. We can continue affirming Cesar’s goal of human justice and equality by becoming social activists. We should also aspire to become not only senators and judges but also writers, producers, and directors and make our own movies.

Anita Quintanilla’s family has lived in the Austin, Tx., area since before it became Texas. She went to UT-Austin from 1968-73 taking time off each year to travel alone to Mexico City, Los Angeles, and then the East Coast. She worked with the UFW staff in NY and Boston and relocated to LA in 1976 to work on a political campaign for the UFW. After organizing farm workers and being a body guard for Cesar Chavez she continued her activism in San Francisco before returning to Austin in 1999 with her son and daughter.

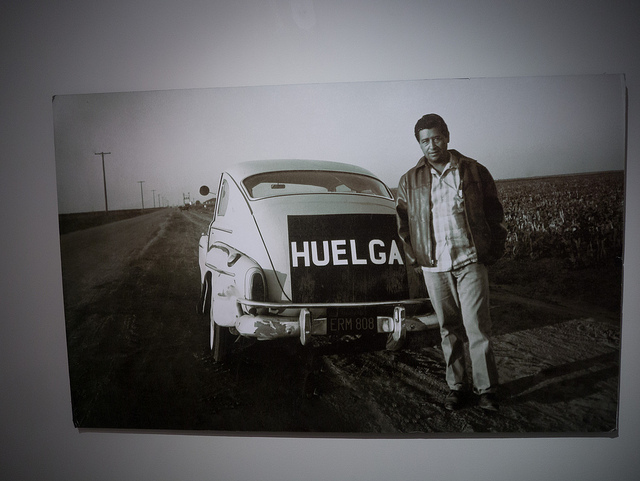

[Photo by Jay Galvin/Flickr, Wikicommons]