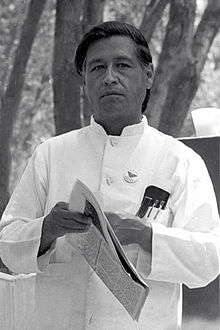

Cesar Chavez, the Undocumented and the Chicano Movement

By Alfredo Gutierrez, NewsTaco

(Cesar Chavez, the Undocumented and the Chicano Movement is excerpted from To Sin Against Hope, by Alfredo Gutierrez, Verso Books, 1010 Jay Street, Brooklyn New York 11201. First published 2013. All rights reserved)

The admiration, even veneration in which Cesar Chavez was held by the young men and women of the Chicano generation is perhaps incomprehensible to someone born years later. Cesar’s story will always be entwined with rise and decline of the Chicano movement. He inspired a generation of Mexicanos to rise up and break the mental shackles of docility and compliance that had characterized generations of earlier Mexicano leadership and to rise up and fight injustice. Hollywood, in a film directed by Diego Luna and starring Michael Peña has tried to capture the moment and the man as he and the movement ascended in influence but that would be impossible. Cesar was a complicated, difficult often contradictory man who in the end was responsible for the his own decline and that of the Union he built.

José Angel Gutiérrez, the enfant terrible of the Chicano movement and a founder of La Raza Unida Party, described Cesar as “the embodiment of a Chicano. Chicanos see themselves in Cesar: clothes, personal style, demeanor and commitment.” Luis Valdez, the playwright and director of Teatro Campesino, approached Christian symbolism in relating Cesar’s importance to the movement: “Without realizing it we already had the leader we were waiting for. It was Cesar Chavez, and he was there slowly burning, poor like us and telling us, suggesting to us what we should do—never ordering us—and little by little we began to organize around him . . . a man, in short, who had suffered in his very being the trials of all Mexican people in the United States.”

The poet Richard Perez fully embraced the iconography of Christ:

With a book of Gandhi in his hand, Like a hero in a decadent world Searching for justice in a contract The Chicano walks proudly

He suffers like a heretic

Suffers martyrdom like Christ

Suffers for suffering is the price

For he who loves the flame of love, the lily

But he is great in his humility

And in all he truly believes

Because he is the only way

That is touched by the redeeming faith

From Organizer to Saint

From Organizer to Saint

By the time I met him, Cesar was talked about more like a saintly mystic than a union organizer. We university students had heard of house meetings with workers, and the rumors of a coming strike. Finally we came upon a mimeographed flyer announcing a meeting where Cesar would speak. A bunch of us cajoled a car and drove ourselves to the shabby union hall at the very margins of Phoenix. The place was packed with women and men and a mob of kids. By our clothes and demeanor we were clearly not farm workers, and were stared at suspiciously but otherwise treated politely. After a while a short fellow stood at the front of the hall and began to speak. The room quieted. This is an important guy, I thought; he is probably going to introduce Cesar. I waited. I expected a Chicano Martin Luther King that would rivet us with a preacher’s soaring oratory. My mother had dragged me into plenty of evangelical church meetings, so I knew a good hell-and-brimstone sermon, in Spanish or English, when I heard one. After a moment I realized this was Cesar. He was unremarkable. He was humble, certainly not dressed like a preacher or a priest, indistinguishable from the men who listened to him reverently. His voice was not powerful, it quivered and was often delicate. I was not impressed. But over the next few days his words, the serenity that seemed to surround him and the obvious impact he had on everyone in that room kept coming back to me. It was not long before I was volunteering with the Union.

The End of Chicano Idealism?

In the course of the next few years I left the fields, returned to school and in a short time I was elected to the Arizona State Senate. The Chicano movement that inspired a generation to break with the docile and compliant leadership that distinguished the Mexicano community for decades was fading away. Perhaps no mass movement can possibly span a decade without losing its energy. Perhaps the Chicano movement was destined to recede slowly at first and then fade into memory. The movement indeed lost its energy, but it also saw its greatest hero, the one constant light of hope and resistance, damaged and diminished. Perhaps it was this that signaled the end of Chicano idealism.

Chavez Against “Illegals”

Cesar Chavez had as early as 1969 undertaken major public actions opposing “illegals”; that year he was joined by the Rev. Ralph Abernathy and Senator Walter Mondale on a march from Coachella to the Mexican border to protest the use of undocumented workers by California growers to break the strikes in the fields and to undermine the union agreements that had been reached. Still, the power, mystique and charisma of the man were such that immigration justice advocates cringed but remained silent. Cesar continued to claim that the Union would have won more victories, and that those that were in place would not be in jeopardy, were it not for the “illegals”. Some close to the union would quietly comment to each other that most members of the Union were recently arrived from Mexico and undoubtedly many were undocumented. By the time of my election to the Senate it was becoming evident that Cesar and the Union were out of step with the consensus forged by Chicano organizations and even with the more conservative Mexican-American organizations who at one time shared his point of view. Cesar’s isolation became even more pronounced in July of 1974 when Union officials were quoted in an AP story as saying: “Aliens were depriving farm workers of jobs and presenting a threat to all people.”At that point a coalition of incensed Latino organizations answered with an unprecedented open letter, part of which declared that “all workers have the right to seek work in order to support themselves and their families . . . when we ask for the deportation of all workers who have no visas we are attacking good Union brothers and sisters who have no visa but would never break a strike.” The letter’s conclusion was particularly loaded: “The [employers’] traditional response was to deport not only the leaders of strikes but the workers themselves. Thus when a Union calls on the US Immigration Service to help them it is calling upon a traditional tool of employers and the United States Government.” There had been rumors amongst activists for years that the Union was calling la migra and reporting undocumented workers. By the time the coalition letter was sent they were no longer rumors. In the spring of 1974 Cesar publicly launched the Campaign Against Illegal Aliens, urging organizers to find and report “illegals” and encouraging the government to ramp up deportations.

The “Wet Line”

By the fall of 1974, though not yet having completed my first term, I was elected Majority Leader of the Senate by my colleagues. The honor also meant that I was immediately thrust into issues that until then I could choose to ignore. One issue that could not be ignored was the “wet line” that the Union had established at the Mexican border near Yuma, Arizona. As part of the Union’s Campaign Against Illegal Aliens, Cesar appointed his cousin Manuel to establish observation points along the border where the undocumented were known to cross. The observers sought to actively persuade the crossers to go back; failing that, the observers were to call the Border Patrol to pick them up. The Border Patrol rarely showed up, I was told, and the consequence was that wet-line thugs would beat the undocumented and force them to return to Mexico. There were many reports of beatings from organizers and activists I trusted and had known for years. None would confront Cesar, but they wanted it stopped before it became a public relations nightmare, and they wanted it stopped because though they loved Cesar, they bitterly opposed his policy. Over the years I have met with even more organizers who were in Coachella or Yuma at the time. All have repeatedly confirmed that the wet line was basically a bunch of paid, roaming thugs under Manuel’s direction.

A Meeting With Cesar

A Meeting With Cesar

At my request, Cesar and I met in a mid-town Phoenix hotel restaurant to discuss the wet line, and his growing public support for mass deportations of a magnitude not seen since the repatriations of the 1930s. I was the twenty-eight-year-old majority leader of the Arizona State Senate meeting with an icon, a legend, a spiritual leader, a mentor—a man I had been in awe of for over a decade. In a hesitant, halting manner I argued that the wet line had to stop immediately and that Cesar should reconsider his support of mass deportations. I was the supplicant and he the master. The meeting was uncomfortably tense and brief. Cesar’s answers were practiced: those of us who were not in the fields could not understand what was at stake; once the Union established labor contracts even the illegals would benefit, thus his actions were for their own good. I never told Cesar how close I came at that moment to shouting over him. “For their own good?” I almost asked in disbelief and anger. But he was Cesar, and I fell silent. He confirmed the existence of the wet line, but he adamantly denied that beatings or violence of any kind were taking place. And with that the meeting was over. Cesar got up and left, his close friend Bill Soltero, the leader of the Laborers International local in Arizona who had accompanied Cesar, hurried after him. Lunch was left uneaten. Cesar had made his point. He would not back down.

Or so I thought.

Then, when the situation seemingly could not get worse, the US Attorney General William B. Saxbe announced that the Justice Department would deport one million illegal aliens. Saxbe proudly added that the United Farm Workers fully supported the deportations. The announcement electrified the Chicano community. Calls for Saxbe’s resignation were immediate, and the tactful phrasing and gentle rebuke that had hitherto characterized criticism of Cesar ended. The criticism was now public, direct, and unrestrained.

The Tipping Point, The Dance Back

On November 22, 1974, the San Francisco Examiner published a letter to the editor from Cesar where he carefully danced back from his seemingly immovable position. The historian David G. Gutiérrez attributed the shift to Cesar’s finally seeing his support weaken: “Aware that he desperately needed to maintain his base of support amongst urban Mexican Americans—particularly Chicano activists and students—Chavez was compelled to reassess his position on this explosive issue.” In the letter Cesar flatly denies Attorney General Saxbe’s claim that the Union supported the deportation of one million undocumented laborers. In fact, he goes on to charge the Justice Department itself for “the mass recruitment of undocumented workers for the specific purpose of breaking our strikes . . .” The Saxbe plan that the Union had, according to the Justice Department, supported was now “a ploy towards the reinstatement of a Bracero program which would give government sanction once more for the abuse of Mexican farm workers and in turn of farm workers who are citizens.” And, perhaps most surprising of all, the letter’s final paragraph began with a commitment that the Union “will support amnesty for illegal aliens and support their efforts to obtain legal documents and equal rights including the right of collective bargaining,” because, he concluded, “the illegals are our brothers and sisters.”

The Damage Done

From “wets” deserving of deportation to “our brothers and sisters” deserving of amnesty was perhaps too great a distance to bridge in a letter to the editor. It was certainly intended to quell the anger, but to many activists the letter was insufficient and unconvincing. Although the criticism of Cesar did subside, the damage had been done. The Chicano Movement was already depleted by the War on Poverty’s long reach and insidious effects. It may be that for the remaining idealists, to witness Cesar as a flawed human being espousing discredited and shameful views was too troubling to bear. Cesar continued to personify the Union even as its membership shrank, its victories grew sparse, the young idealists drifted away, and the reverence in which he had once been held diminished. Only after his death would Cesar become once more the spiritual leader, the symbol of courage, idealism, sacrifice, selflessness, and quiet wisdom that inspired a generation.

Alfredo Gutierrez was first elected to the Arizona senate at age 25, Alfredo served as the majority and minority leader in the state senate. During the 1970s, as the Senate Majority Leader, Alfredo was arguably the state’s most powerful elected official. He is the author of To Sin Against Hope.

[Photos/Wikicommons, Salina Canizales]