How a U.S. Guest Worker Program Worked Before

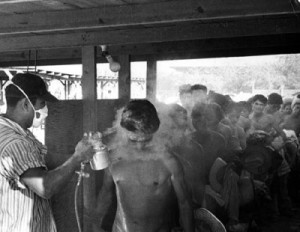

With the Obama administration and the bipartisan senate Gang of Eight poised to move on comprehensive immigration reform soon, which may include an agricultural guest worker program, our country has much to learn from our labor history. During WWII, the Bracero program allowed Mexican men to enter our country legally to harvest fields. This is how my father entered the U.S. During WWI, Mexican laborers were sprayed with pesticide before they could enter our country. In 1917, one 17-year-old maid led a protest, the Bath Riots, against this toxic treatment.

Nine years ago, this essay about my father’s labor in Texas opened the doors for my writing on National Public Radio. I share this essay again to remind our country about our dependence on immigrants. With over 12 million undocumented immigrants in our country, we need reform–not irrational deportations.

In Illinois and four other states, undocumented immigrants are eligible for driver’s licenses. As of last fall, DREAMers, younger undocumented immigrants without criminal records, can obtain work permits. The political voice in support of comprehensive immigration is stronger than it has ever been. May this essay remind us of the human aspect of our arguments and of the need for reform–soon.

_________________

For a kid in Chicago’s Little Village Neighborhood, the only thing worse than being called a wetback was being called a Brazer. Wetback just questioned your US status–but who cared? Brazer, however, insulted your appearance.

During the early 80s, if someone wore a blue guayabera and black shoes with white socks for school pictures, we called him a Brazer. If we saw a girl walk down the street with long braids we yelled, “Brazer!” On 26th Street once, I saw a dark- faced man in jeans, cowboy boots, and a baseball shirt with S-U-E ironed-on the front; I thought, “Brazer.” None of us knew what the word meant. We just heard it and used it to talk about those who spoke with too much of an accent.

It wasn’t until college that I learned that the word came from “Bracero:” a Mexican man who was contracted between 1942 and 1964 by the U.S. to do agricultural work with his “brazos,” his arms. My father did this type of work, so he was a Brazer. I don’t know if I felt more guilt or more shame for thinking that a Brazer was the most humiliating thing a Mexican could be.

The Bracero Program was established during the Second World War to help solve the U.S. agricultural worker shortage. It allowed American farmers to hire Mexicans to harvest fields. Both sides saw the rewards: good labor that was cheap and steady work that paid. The law was extended in 1951.

Men from all parts of Mexico came to border towns, signed contracts, and waited for the chance to work. In 1956, more than 80,000 of them passed through the El Paso, Texas Center. Braceros stood in corrals until they were chosen for a physical exam. If they passed, they were awarded work permits for days or for months depending on the contractor. Once the permit ended, the Bracero was returned to Mexico. Since the men came from rural towns, many extreme in poverty, the guarantee of at least thirty cents per hour was a fortune.

One day in 1957, my father Raymundo, left his farmhouse in St. Rita, Coahuila (a tiny town of dust and desert). His father had sent word that there was work up north. He went to Piedras Negras, border to Eagle Pass, Texas, to meet-up with his father, Ramón. Once there, my 21-year-old father rode the bus to Monterrey to sign the mandatory contract. My father was lucky. Because my grandfather spoke good English, the U.S. contractors hired him to select workers. My grandfather naturally chose my father to work. Men who weren’t selected, my father remembers, killed their hunger by eating mandarin peels.

A Bracero had to look strong, healthy. Disease or physical limitations excluded him immediately. To prove that they had farm experience, men would rub rocks between their hands to make them rough. Soft hands meant no opportunity. My grandfather would stand above the corral and point “Tú . . .Tú . . . Tú” to men who looked up with ambition.

In Ciudad Juarez, on the other hand, the situation was different. Guillermo Rosales, a family friend, was a Bracero there. He tells how white men waited for them with plastic gloves as they clustered underneath the sun. They were told to strip; then each man was examined. “Lo querían enterítamente entero,” they wanted you completely whole, explains Rosales, emphasizing with his eyes. Then the men were sprayed with pesticide to kill bacteria, disease, and lice.

My father’s experience was nothing like this. If it had been bad, he still wouldn’t have complained. His attitude toward hard work was to do it. Pictures of him in his 20s show his face firm and arms thick from turning over earth. Without a mustache or a beard, my father looked into the camera calmly, stern and made sure his hair was pushed back, just so. At 5 foot 6, he had a chest broad enough to breathe the Texas air and carry harvests on his back.

Whatever discomforts my father felt during this time because of the sun or because of the work, I can’t know because he won’t say. “What’s the best memory you have of being a Bracero, Dad?” I ask. My father bursts out laughing to hide the nostalgia he’s afraid will bring him to tears: “I had a lot of girlfriends.”

Not everyone had it this good. In Chicano lit class, I read And the Earth Did Not Devour Him and saw the pain that campesinos felt as they stared into the dirt. I ask over and over about illness, racism, abuse, or loneliness. My father shakes his head until I understand this life for him was pleasant. But I also understand that others were abused.

The first wave of Braceros unknowingly authorized pay deductions for their retirement when they signed contracts in English. Advocates estimate that the total amount withheld, with interest, exceeds 150 million dollars. Not surprisingly, the money can’t be found; most Braceros don’t expect it to be.

But the money is not the only thing that’s disappeared. Many people with a father who picked crops have forgotten how that work made our life more comfortable. In the 1960s, my father stopped working with the land, found his way to Chicago, and became a mechanic. The scars from both jobs have never left his hands. At seventy-four, his palms have never softened. At twenty-six, I began to chance my dreams with writing because my father chanced his upon a word.

Brazer. Kids on Chicago’s Southwest Side still assign the term. They’re unaware that this word for outcast once gave so many hope. They overlook the calluses on granddad’s hardened hands as he gives out Sunday dollars.

Instead, they hurl the word—Brazer–at anyone’s who’s different. And it lands like punch. Or a slap, from a hand that isn’t callused and barely has a scratch.

[Photo by National Museum of American History via @ZinnEdProject]