Latino Churches Adapt To Appeal To Growing U.S.-born Latinos

By Jaweed Kaleem, Huffington Post Latino Voices

By Jaweed Kaleem, Huffington Post Latino Voices

While other kids her age drifted away from the faiths of their childhoods, Pardo was sure she believed in God. But as the daughter of Colombian and Nicaraguan immigrants, she wasn’t sure she fully understood him in Spanish, her second language — and a distant one at that.

So when the Protestant congregation instituted a controversial effort last year that included encouraging youth like Pardo to switch to worshipping separately in English, it immediately piqued her interest. She just had to break the news to her parents.

So when the Protestant congregation instituted a controversial effort last year that included encouraging youth like Pardo to switch to worshipping separately in English, it immediately piqued her interest. She just had to break the news to her parents.

“It was never a faith of my own, it was ‘oh, my parents’ religion’ or ‘my family faith’ and I never saw the personal connection between me and God,” Pardo, now 20, said last Sunday after a service at Sunset Church of Christ, an English congregation that shares a building with the church of her childhood but has for much of its history operated separately from it. “I told them I wanted to go, but I told them I wanted to go in my own tongue and culture. Not theirs.”

As the nation’s Hispanic population has grown to 50 million, so too has the Spanish-language church, one of the largest segments of U.S. Christianity. But compared to previous decades, when the growth in the Hispanic population came from immigration, and when many of the nation’s biggest Spanish-speaking congregations blossomed, the growth of Hispanics in the last decade has been led by second-generation and third-generation Hispanics, such as Pardo and her peers. The latest national census showed that native-born Hispanics, who tend to prefer English, now account for nearly two-thirds of the group.

While it’s become common wisdom that English-speaking churches will shrink as younger generations, who are typically less religious, become the majority, the Spanish church — known across denominations for its religious fervor — is battling to keep its youth in the faith. It’s having to budge on one of its biggest points of pride and identity, its language, to hold on to them.

Of the thousands of Spanish-only churches in the U.S. that formed decades ago to serve growing communities of immigrants from Latin America and the Caribbean, several began in recent years to expand beyond their traditional culture and tongue as a means of survival, meeting varying levels of resistance and success.

The change is happening throughout Hispanic churches and neighborhoods, from the Mexican-American communities of Texas and California to the Puerto Rican enclaves of New York and in South Florida, where a mix of Cubans, Colombians, Venezuelans and Central Americans make up many of the region’s Spanish-language congregations.

Oftentimes, members and pastors are torn: Do they hold on to language and heritage, losing members and relevance? Or do they adapt?

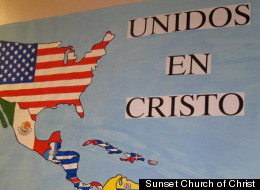

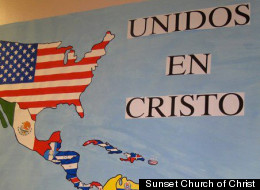

At Sunset, a dual-language, dual-congregation church building that for many years was effectively two churches sharing property, elders, ministers and lay members are grappling with such change.

***

Like many churches in South Florida, Sunset has long attracted English and Spanish speakers. For 20 years, it’s had a Spanish congregation, whose membership has continually grown because of new immigrants becoming more active and younger over the years compared to the English side, which traces itself to a small house church established 101 years ago. While it’s going through its own transition today, Sunset is a result of an earlier merger of two churches, one which established Spanish services in 1968 to cater to a growing Cuban immigrant population.

Generally, the church’s English side is made of a mix of non-Hispanic whites, blacks and a smattering of members with other ethnic backgrounds. A few Hispanics attend the English services, too, but most end up on the Spanish side. Sometimes, it’s out of necessity because they speak little or no English. Many other times, it’s because they want to raise their kids not only in the same faith they were raised in, but the same faith in the same language. Together, the congregations have 500 members.

Ministers say that if the youth aren’t encouraged and given the option by clergy and their parents to attend church in English, they’ll leave for more English friendly Hispanic churches, such as mega-churches that have proliferated in part because of their targeted appeals to specific age, language and cultural-based groups.

“When you walk into Sunset, you have to pick one: English or Spanish. The way our ministries are set up, you can’t really (have families) do both,” said Jim Holway, a bilingual pastor and professional church planter — someone who starts new churches. Holway, 53, landed at Sunset seven years ago to use it as a base to coach pastors of new Hispanic churches and congregations in the region and in Central America, but he quickly realized the bulk of his attention was needed at Sunset itself. “I started attending the church and kept on seeing these kids who were becoming teens and disappearing. Where were they going? Sometimes, it was to a church that offered them services in English. Other times, they would just drop out of church completely.”

Holway, who was raised in Virginia but spent his adult life learning Spanish as a missionary in Argentina, is one of a core group of ministers spearheading an effort to transform Sunset into a successful multilingual church, where kids can speak and worship in English, parents can speak and worship in Spanish, and, he hopes, “each can grow in Christ and get along.”

Ministers, struggling with the changing demographics of their congregations, have attempted a variety of means to attack the language divide. Older, monolingual pastors who separately ministered to different congregations are gone. New, younger bilingual ones have come in. The church has instituted a quarterly bilingual worship service, where hymns and prayers are alternatively said in English and Spanish (“It’s exhausting and confusing to people who only speak one language,” said Holway). Elders have considered having services in English for everyone, where live Spanish translation is done via headset, (“People think that is unfair to the Hispanics, and if it’s in Spanish, the English speakers would be bothered,” he said).

The congregations have some aspects in common. Iglesia de Cristo en Sunset uses a Spanish version of the same worship study book throughout the year as Sunset Church of Christ, and both congregations sing their Sunday praise a capella. But there are differences. In the English congregation, a recent Sunday’s worship was full of a mix of Negro spirituals and 19th century Protestant hymns, while the Spanish side plucked lyrics from the Cantos del Camino, a popular hymn book that draws from a mix of traditional Christian songs from Spanish-speaking countries. During a 20-minute intermission between classes and worship, when both congregations found themselves in the hallway, and church ministers had set up donuts and coffee to entice the groups to mingle. A few of the Spanish side’s members drank Cuban espresso in one corner, while English members across the room chatted over coffee.

Recently, ministers have considered a plan to scrap the church’s Sunday schedule, which currently allows both worship groups and their Bible classes to meet at different times and effectively avoid each other. Classes and worship — now spread over a five-hour period on Sunday mornings — would happen at the same time under the new plan. That way, ministers say, families would be more likely to send kids to English classes and services while parents go to Spanish ones without extra trips to the church or any lag time spent in the halls.

All that is, of course, if the membership goes along with it. Many younger members, those in their teens through their 40s, are on board. But for those in their 50s and above, the situation is far from settled.

Last January, after years of studying membership patterns, plate collection statistics and participation in youth and Bible study meetings, church leaders pulled their congregations together to explain the new Sunset. They played YouTube videos that had been produced in both languages, and went over a PowerPoint presentation projected onto the auditorium screen usually reserved for hymn lyrics. Called “One Church, Two Languages,” it made a two-prong argument. First, South Florida and the nation are melting pots, it said, and churches need to adapt. And in a denomination whose hallmarks include strict, literal readings of the Bible, it said the coming changes were part of God’s plan.

It quoted Acts 6:1-4, which describes conflicts between Jesus’ Hebrew-speaking and poor Greek-speaking disciples, in which the Greek speakers said their wives were being discriminated against in the food lines. The apostles called a meeting of the disciples, telling them that it would be immoral to stop feeding the poor or favor one group over another. The presentation likened the English and Spanish speakers to Hebrews and Greeks. It referenced Galatians 3:28: “In Christʼs family there can be no division into Jew and non-Jew, slave and free, male and female. Among us you are all equal. That is, we are all in a common relationship with Jesus Christ.”

Below, in bold letters, it said: “There is neither LATINO nor ANGLO. No hay LATINO ni ANGLO.”

In theory, everyone got it. In practice, not as much. Some Spanish speakers were suspicious the church would turn completely toward English, losing any relevance to cultures from their native countries. Some English speakers weren’t comfortable with the style of the Spanish congregation, where kisses and hugs take the place of handshakes, and where worship can be a little less formal and a bit more social.

“It may seem like small potatoes. But these are the kinds of things that altogether make a church work,” said Jeff Hinson, a church elder, during a recent gathering of Sunset’s leadership team. “Some parents want kids to still maintain their identity, and we think they should, but we are not sure church is where that should happen. For us, it’s better taught in the home.”

“There’s some resistance to that among parents,” including…

This article was first published in Huffington Post Latino Voices.

Jaweed Kaleem is the national religion reporter for The Huffington Post. Prior to HuffPost, he was the religion reporter for The Miami Herald, where he worked since 2007 and was a member of a breaking news team that was a 2011 Pulitzer Prize finalist for its coverage of the 2010 Haiti earthquake. He has produced radio reports on religion for Miami’s WLRN 91.3 FM and PRI’s The World. Before religion reporting, he was a general assignment reporter at the San Jose Mercury News, Detroit Free Press, Lexington (Ky.) Herald-Leader and McClatchy Washington Bureau.

[Photo by Sunset Church of Christ]