Mexico’s Day of the Revolution – A Holiday Worth Celebrating

By Phillipe Diederich, Voxxi

By Phillipe Diederich, Voxxi

November 20th is Mexico’s Día de la Revolución (Day of the Revolution). It’s not Independence Day, and it’s certainly not Cinco de Mayo, which celebrates the Mexican victory over the French during the battle of Puebla in a war the Mexican’s eventually lost. What is Mexico’s Day of the Revolution about then?

Mexico’s revolution started in 1910 and ‘officially’ ended with the Constitution of 1917. But fighting, and social repositioning in the country went on through the mid 1920s. The Revolution ended the 33-year dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz, and set Mexico on a modern socialist path.

During the time of the Diaz regime Mexico’s economy boomed and was sometimes compared to the economies of Great Brittan, France and Germany. Diaz, ran a centralized government, and gave substantial land and tax breaks to foreign companies, so the Mexican economic boom was only being felt by the rich, and the foreign corporation that were given preferred status; mines, railroads and other concessions.

Day of the Revolution – History

Day of the Revolution – History

A series of events brought about the Mexican Revolution and the toppling of the Porfiriato, as the Diaz regime was known. Not only was there a huge economic gap between the 99 percent poor and the 1 percent rich, but the government also privatized the ancestral and communal lands of hundreds of thousands of peasants. At the time, 95 percent of the land in Mexico was owned by 5 percent of the population.

In 1910, Francisco I. Madero, a statesman from a wealthy family, campaigned to become the next president of Mexico, but Diaz had Madero arrested and declared himself the winner of the election. Madero escaped from prison and is credited with starting the Revolution when he launched the Plan de San Luis Potosi in 1910, and calling for armed revolt on November 20th, 1910.

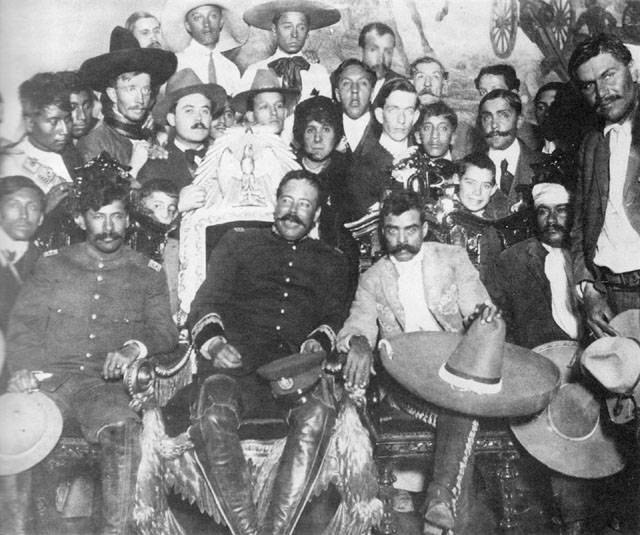

In 1911 Diaz resigned and Madero was elected president, but was toppled in a military coup led by General Victoriano Huerta and killed in 1913. While all this political positioning was taking place, Pancho Villa was stirring things up in Chihuahua as a Maderista, and Emiliano Zapata was rebelling for peasant rights in Morelos, in southern Mexico.

When Madreo supporter and Primer Jefe of the Constitutionalist Army, Venustiano Carranza, marched triumphantly into Mexico City in August of 1914, he broke with revolutionary leaders, Zapata and Villa. Carranza became president and established the Constitution of 1917, which to many became the official end of the revolution.

The Constitution of 1917 stripped the church of much of its power, which led to uneasiness between the church and the government. In 1924, when Plutarco Elias Calles took over the presidency, secularist laws were applied stringently. Groups of Catholics revolted in 1926, and this gave way to what became known as the Cristero War.

The early 1920s saw many ideological changes as Mexico reestablished relations with the Soviet Union. The first murals by Diego Rivera, Jose Orozco and David Siqueiros were created opening up an era that openly embraced Mexico’s indigenous heritage, and meztisaje. Also, as a result of the 1917 Constitution, Mexico’s relationship with the Soviet Union, and land and social reforms pushed on by Zapata, Villa and others, the first national worker’s union, Confederación Regional Obrera Mexicana, was created in 1918.

But one of the most important accomplishments of the Mexican revolution of November 20, 1910, was national pride. The revolution gave peasants and workers a sentiment of worth, that they have rights, and that they can fight for these rights. It’s is one of the reasons popular protests and movements like Yo Soy el 123, or the Zapatista uprising in Chiapas can happen today after 100 years since the ‘first’ revolution, in a country that is closer in reality to the Porfiriato, than the ideals of the Revolución.

This article was first published in Voxxi.

[Photo courtesy Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia]