Day of the Dead: A tale of a Mexican Halloween Tradition

By Tony Castro, Voxxi

By Tony Castro, Voxxi

It was the evening after Halloween, when I had gone trick-or-treating dressed in black from head to toe with the white bones of a skeleton hand-embroidered on my costume.

Doña Juana made the costume, telling me it was magical because she had sewn on bits from bones of a real cadaver.

“No le creas,” my mother said, always disbelieving the fantastic stories Doña Juana habitually told.

“No le creas,” my mother said, always disbelieving the fantastic stories Doña Juana habitually told.

“Es otro chiste de tu tia.” (“It’s another of your aunt’s jokes.”)

Still, I thought I could feel bones in my costume. I wore it to bed like pajamas and kept it on the next day when I visited Doña Juana for the weekend.

“Con esos huesos de la muerte vas a poder ver tu vida pasada,” Doña Juana said to me after my parents dropped me off at her home. (With those bones of death, you will be able to see your past life.)

It would be years before I understood Día de los Muertos or Day of the Dead. As a five-year-old, growing increasingly confused between my English and Spanish halves, I thought of Day of the Dead as Spanish Halloween, only celebrated longer.

Spanish Catholic Halloween.

Catholicism had an eeriness about it that had frightened me from the moment I had wandered off to a darkened alcove of our church and discovered a life-sized crucified Christ, captured for eternity in excruciating agony.

Learning the traditions of Day of the Dead

Learning the traditions of Day of the Dead

Catholicism and Day of the Dead shared many of the same symbols.

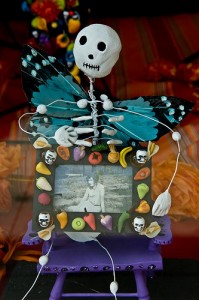

The altars and santos Doña Juana and other relatives used to offer their prayers and rosarios were the same ones employed for their Día de los Muertos rituals: the offering of pan de muertos (bread of the dead) and other baked and candy goods made into edible skulls, crosses and cadavers to the souls of the dead.

The world of Doña Juana was also one of incense and Estafiate. Her home smelled of both as she seemed always to be burning incense and brewing Estafiate tea, good for any malady, including death.

There was a large jug of freshly brewed Estafiate tea in an old wooden wagon Doña Juana lugged behind her at sundown that evening when we set off for the cemetery several blocks away.

We were part of a long procession that arrived at the graveyard for an all-night vigil of communion with the dead. Burning candles reflected off the tombs and gravestones that had been scrubbed clean and decorated.

My grandfather’s gravestone shined especially bright. It was fairly new. He had died just a few months earlier.

Don Jose Angel and I had been unusually close. I had grown up spending every weekend with him, amused by his intricate war stories of the Mexican revolution in which he had fought and his tales of Greek heroes, which he wished he had been.

“The only heroes more tragic than the Greeks are the Mexicanos,” he often told me. “They have no Homer to tell their glory.”

When he died, my grandfather had been reading an old copy of The Iliad translated into Spanish. The women who found him couldn’t read and told all his friends that Don Jose Angel, a lapsed Catholic, had been reading the Bible on his death bed and had found God in his last hour.

I knew this wasn’t true, but no one would listen to me. They buried my grandfather with two religious services. The Catholics in my family insisted on a funeral Mass. The Pentecostals in the family claimed that the Bible he had been reading when he died was a non-Catholic Bible.

At the cemetery, they turned the burial into a raucous holy-roller sideshow.

Only I knew that Don Jose Angel wanted to be cremated on a funeral pyre like the Greeks.

At his grave, Doña Juana lit a candle and began laying out the feast she had brought. I knelt in front of the gravestone and began praying.

“Please forgive me, Don Jose Angel,” I said. “Please forgive me for letting you down.”

As I bowed my head and prayed an Our Father, I felt the candlelight’s reflection on the gravestone glow warmer and brighter.

I started to move back until I looked at the gravestone and saw Don Jose Angel’s face smiling back at me.

“You have not let me down,” he said. “You are the reason I have come back for tonight.”

For most of the night, I listened to Don Jose Angel tell me the legend of Achilles, the greatest of the Greek warriors, one last time.

At sunrise, I awoke in Doña Juana’s arms. It was time to return home.

But I had one last thing to do.

I ran around the cemetery collecting dead twigs and branches and with Doña Juana’s help began piling them into an altar-like pyre next to Don Jose Angel’s grave.

When we were finished, I stripped off the Halloween costume and felt for the cadaver bones that Doña Juana had sewn on.

“You won’t get mad at me?” I asked her.

“I told you the costume was magical,” she said. “So use its magic.”

I laid the costume on top of the funeral pyre and lit the bottom twigs with one of the candles that was still burning.

In seconds the dry wood began crackling. Flames danced around the costume before it began burning as well, lighting up the early morning sky.

My grandfather’s funeral was now complete. He finally had the hero’s funeral he had dreamed about.

This article was first published in Voxxi.

Los Angeles-based writer Tony Castro is the author of the critically-acclaimed “Chicano Power: The Emergence of Mexican America” and the best-selling “Mickey Mantle: America’s Prodigal Son.”

[Photos by laihiu and St0rmz]