Latina Working Mothers Can ‘Have It All’ — By Adjusting Their Expectations

By Kalyn Belsha, Voxxi

By Kalyn Belsha, Voxxi

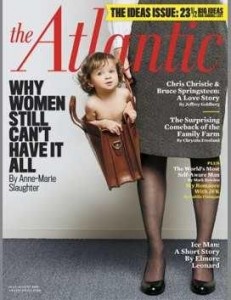

In a recent article that went viral, Anne-Marie Slaughter, a mother of two and the former director of policy planning for the U.S. State Department, took a bold move by saying that right now, in America, women can’t have both professional success and an involved family life, given the current economy and the way our society is structured.

Her assertion that “women still can’t have it all” created a lot of dialogue on the web, much of it centered about public policy that needs to change to make it easier for parents to have a happy work-life balance.

But in an interview with the New York Times, Slaughter, who was also the first female dean of Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, says she thinks the issue is less a policy problem than an issue with American social culture.

“The decision to step down from a position of power — to value family over professional advancement, even for a time — is directly at odds with the prevailing social pressures on career professionals in the United States,” she wrote in the July/August issue of The Atlantic. “Many people in positions of power seem to place a low value on child care in comparison with other outside activities.”

One of the solutions Slaughter proposes is advice that will be familiar to many Latinas: “revalue family values.”

Reports on career advancement have long stated that Latinas face barriers in the workplace because they place a high priority on family, including their extended family, and more often have elder care responsibilities — which is something white managers and co-workers may not understand,according to a 2003 report on Latinas in the workplace.

To create an atmosphere that is hospitable to Latina professionals, the report continued, managers should “focus on productivity at work rather than time in the office” and “create an open dialogue… (so) you understand how individual employees define ‘family.’”

The idea that we can change society by changing the conversation around valuing family time is an interesting one. Slaughter suggests taking ownership of your role as a parent by being honest with your boss and co-workers about the time you are setting aside for your children — and to stop apologizing if you can’t work late for family reasons.

To be certain, there is room for improvement on government policy that dictates maternity and paternity leave. The Family Medical Leave Act only provides 12 weeks of unpaid leave to new mothers and fathers, or 12 weeks to tend to a sick child, spouse or parent.

But that law only applies to employees who work consistently and for companies larger than 50 staffers, which excludes much of the U.S. population. And for those it does cover, many low- and middle-income employees cannot afford to take the time off.

This disproportionately affects Latinos, who despite falling birth rates among Latinas, still have the largest family sizes in the United States when compared to white, black and Asian families, according to the latest Census data.

The United States has long been urged to catch up to other countries around the world — such as Spain, Cuba, Mexico, Chile, Colombia and Venezuela — that offer at least three months’ paid leave for new mothers.

But U.S. policy won’t change until working mothers have the confidence to equally value their time spent as a professional and caregiver. Or until they can see their career paths not as a gradual ascent ever-upward, but as what Slaughter calls “irregular stair steps, with periodic plateaus.”

For many women, like Eunice Smith, a Colombian-American raising five children in Chicago, developing that mentality is a process.

“I value myself enough to know that the time I invest with my children is worth, at least to me, more than a full-time job,” said Smith, 36, who until December was an executive director of a local nonprofit for more than three years. “Through my work and personal experiences I have learned not to sell myself short.”

Or perhaps what working women need to do is to redefine what it means to “have it all” — and to accept that it might mean not being perfect at everything.

This article was first published in Voxxi.

Kalyn Belsha is a freelance journalist based in Chicago. Her primary areas of interest are language education, immigration policy, changing demographics and Latino community news.

[Cover photo courtesy The Atlantic]