Violence Against Women Act: A Human Face

By Carlos Sanchez, Voxxi

By Carlos Sanchez, Voxxi

Although she lived with fear, this 42-year old mother took the final step in an abusive relationship by calling police. She had arrived in the U.S. ten years ago from her native Colombia and it’s been more than three years since she has last seen the man who broke several bones in her face during a heated argument.

She declined to give her name for her safety.

As the years progressed, fights with her boyfriend escalated from verbal to physical — and it took an emotional toll on her because she was in the United States without immigration papers. She increasingly relied on her abusive partner — a U.S. citizen who could have helped her gain legal permanent status but didn’t — and wasn’t sure she could survive on her own.

“There were people who told me, ‘Don’t worry,’ that domestic violence isn’t silent. Here, nothing happens to women for [reporting] domestic violence…on the contrary they protect you, you won’t get hurt. So, after hearing that, I said I don’t have anything to fear,”’ she told VOXXI.

And she learned about another option — an 18-year-old federal law called the Violence Against Women Act, which allowed her to apply for a visa and set her on the path to residency, so long as she cooperated with police.

But now her life is in limbo because of partisan Congressional deadlock over renewing the law that helped her.

Politicizing the Violence Against Women Act

Under the provisions of the Violence Against Women Act, applicants can obtain what is called a U Visa, which provides an incentive for undocumented women to report their abuse: a path to citizenship.

Congress is currently debating whether to renew this act, which first passed in 1994, and has been renewed with bipartisan support every six years since.

The law was originally drafted by Vice President Joe Biden when he was in Congress. It not only provides undocumented women with permanent residency after showing evidence of abuse, but it also provides funds for protecting them and prosecuting abusers.

A House version of VAWA, introduced by Rep. Sandy Adams (R-FL.), was passed last week. Critics contend it rolls back protections for undocumented women, particularly with the U Visa, because it denies victims legal residency thus eliminating the incentive.

Adams’ version also has a provision that informs the Department of Homeland Security whether the victim is seeking immigration relief. Critics claim that provision provides the abuser with information about the victim’s case when they’re interviewed by DHS. That could perpetuate the violence.

But supporters say that without the restrictions, there’s a potential for fraud, even though no evidence of widespread fraud has been cited yet.

A Democratic version of the bill was passed in the Senate last month; it upholds the U Visa requirements and raises the number of U visas to 5,000 more per year.

“It is disappointing that the Senate has instead chosen to score political points on the backs of victims by inserting provisions that pit one group against another,” said Adams on the House floor last week.

Now with both versions in Congress, the debate has stalemated in a House-Senate conference committee.

Maria Jose Fletcher, a Miami-based attorney who deals with domestic violence and trafficking cases, is rallying against the House version. She says that fraudulent claims are a misconception.

“Based on my experience and the experience of my colleagues and the hundreds of cases that we have filed throughout the years, we know how the checks and balances are already in place during the process,” said Fletcher. “It’s not easy to get these cases approved. A third of the applications that we file get denied.”

Among immigrant women married or formerly married to abusive U.S. citizens or legal residents, 72.3 percent never filed immigration papers. Among those who did file, in most cases, the process was delayed for an average of almost four years because of the abuser, according to a 2000 study cited by the International Journal of Criminology.

In 1996, Congress created special confidentiality protections for undocumented crime victims to try to prevent stalking or unnecessarily allowing immigration enforcement officials from having the victim removed from the United States.

The National Immigrant Women’s Advocacy Project presented seven cases in which the organization claims Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents had used information and collaborated with perpetrators in an attempt to deport domestic abuse victims between 2003 and 2006.

In Denver, for example, an abuser received a victim’s file from an ICE agent. He called the victim and began to harass her, acknowledging that he knew she had filed for a U visa because he obtained the document from ICE. The case opened an internal investigation, but up to this date, ICE has not said what happened, according to the document.

ICE spokesperson Nicole Navas said these cases occurred before the confidentiality provisions were enacted in 2006 by Congress’ re-authorization of the law.

Ira Mehlmen, media director of the Federation for American Immigration Reform, doesn’t think the House provision discourages undocumented women from reporting their abusers. He said that informing people that they are suspects is standard procedure in law enforcement cases.

“You don’t need any sort of provision or special visas to foster that kind of cooperation; this is what police deal with every single day,” Mehlmen said. “In the past people did feel comfortable coming forward and providing information without any expectation that they were going to get some kind of immigration reward.”

He explained that, under the current law, the victim would only be likely to help law enforcement, while the House version makes it the standard for victims to provide more help.

The mother who left her partner didn’t think twice when she called the police the day of her attack. Yet, she was concerned about her situation given her legal status. Before she made the call, a friend told her that she couldn’t stay silent any longer.

She told police what happened and he was arrested. While she was comforted at a domestic violence shelter that she would not get deported, she also knew he posted bail the next day and was freed from jail, she said.

“Obviously, I’m better. I have tranquility with my son. I live fine. I don’t have to cry to ask for food to anyone. My son now has toys, clothes that he didn’t get from his father. He wouldn’t give us anything, now we’re fine. We live in peace,” she said.

“Without the U Visa, it would be like cutting our wings, practically, because it’s the only hope we have of realizing our lives in this country,” she said. “It would be big hit…could you imagine confronting face-to-–face your own aggressor in a court? We have all to lose, it’s not just.”

Carlos Sanchez is National Political Editor of Voxxi. He’s a 30-year newspaper industry veteran, most recently Executive Editor of the Waco Tribune-Herald, State Editor for the Austin American-Statesman and before that he was a reporter for the Fort Worth Star Telegram and the Washington Post.

This article first appeared in Voxxi.

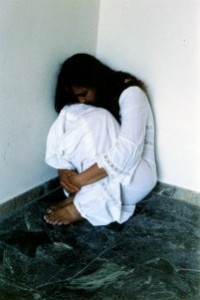

[Photo by ophelia]