My Memories Of Cesar Chavez, And How His Spirit Lives On

When Cesar Chavez visited Austin in 1971, I was unable to personally meet him, but the next year I was able to make up for this missed opportunity when I went to his son’s wedding reception in Delano, California. As I approached this family man for a dance, the “Chavez Mystique” vanished when I noticed how plain and down-to-earth he was. While working with Dolores Huerta in New York City in 1975, I was able to further observe Cesar’s humanness; he spoke at different events, including one occasion with the Kennedys and Shrivers and other dignitaries in Boston.

Cesar’s humility and honesty seemed to dissipate any arrogance that may have been lingering in the air for someone who didn’t really know him. In California in January of 1977, while taking a break from organizing farm workers, I stopped off in La Paz, the United Farm Workers headquarters. While there, Cesar asked me if I wanted to be one of his security guards, mentioning that he felt it was time to have a full-time female guard, adding that he had total trust in me.

I remember one time when we stopped to eat in a park in Sacramento and Cesar told us about a time he went to a huge social event of politicians and celebrities in Mexico City and the hosts of the event offered him female companionship. Cesar was shocked, and the hosts were embarrassed, and quickly apologized. In retelling this unpleasant incident Cesar’s face was very expressive in revealing his reaction and theirs.

On these road trips I usually rode in the “suicide car,” but one time I occupied the station wagon with Cesar and the driver. As we drove through the Central Valley of California, Cesar gave us a detailed account of the UFW history of each town. It was such a pleasure and comfort to hear his soothing voice and such an honor to be privy to his recollections and personal reflections — he sure loved talking! During another trip we all stayed at his cousin’s house in Phoenix, Arizona. Early the next morning I had to go into the bedroom to tell Cesar that it was time for him to wake up; I felt bad about having to disturb his sleep, knowing how much he needed rest. I’ll never forget his sleepy and tired face lifting up from the pillow and turning towards my voice.

At La Paz, located high in the Tehachapi Mountains, Cesar was able to relax a little with the community and his family. He liked to joke around and playfully tease us. One early morning Cesar wanted to celebrate the birthday of Dolores’ eldest daughter, Lori. He managed to convince some of us to get up very early to sing “Las Mananitas” to her after he served us hot Mexican chocolate with tequila in it! He went around offering us more to drink with a quizzical expression on his face; this was one of his less serious ways of celebrating his Mexican heritage. On several social occasions we had there at La Paz, Cesar had opportunities to pursue his love of dancing — which he was very good at. One day some of us joined Cesar in the community garden, as his small, dark fingers sank into the warm soil, he patiently described the many different kinds of chilies present. I was amazed by his wealth of knowledge of plants and the environment.

In one conversation we shared, I told Cesar about how successful we the Chicano students were at the University of Texas at Austin in eliminating non-UFW lettuce in the campus cafeteria. And then I proudly mentioned how we staged a sit-in in the governor’s office one day because we wanted him to proclaim it “Cesar Chavez” day. Cesar responded by telling me how students were such a powerful base of support and how their dedication and commitment helped the union accomplish its goals. This man, who I loved like a father, taught us some hard lessons about being responsible for our actions — that “the buck stops with me.” If we messed up he wanted to hear us say, “Yes, I messed up.” Of course, he also emphasized the importance of learning and growing from our mistakes. Later that year, I left La Paz and the UFW and headed north to continue my social and political activism.

Years later, when I first heard that Cesar died, I was sad but also not surprised. I just knew that with his intense drive for justice he would never slow down in his fight against California’s corrupt agribusiness. Growers constantly made up negative and damaging propaganda to justify their animosity towards Cesar, their mistreatment of workers, and their anti-union stance. The 40-year war they waged against him, with the help of the John Birch Society, the FBI, Republicans and police, finally took its toll on this non-violent warrior.

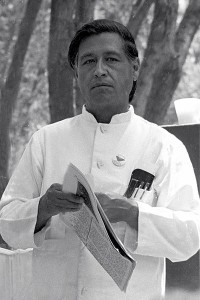

I know Cesar would prefer I write about La Causa rather than about him, but I believe it is very important for people to know the real Cesar. He was not particularly charismatic or a great orator, but people listened to him because he spoke simple truths. Chicanos and liberals built Cesar up to be a larger-than-life leader, a man of, for, and by the people — he was the answer to their and society’s problems and everyone demanded and expected more of him. He was considered a saint, a national labor leader, a Chicano icon, an American Gandhi, a Mexican Martin Luther King, Jr., etc. But he was just an ordinary man in extraordinary circumstances. He was a plain-spoken, unassuming leader who had a great deal of common sense and a practical approach to dealing with issues.

There is now a nationwide effort to win a national holiday for Cesar Chavez. This is supported by many supporters, celebrities and even the President. But even without the holiday, Cesar’s legacy and spirit lives in the thousands who continue to fight for the rights of workers and others who is being treated unjustly.

[Photo By Joel Levine]