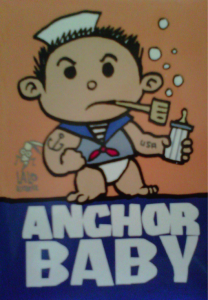

The Ruminations Of A One-Time Anchor Baby

When I was only five years old, the railroad company my father was working for laid him off. His unemployment check was enough for him to survive, but it did not provide enough sustenance for my mother, my sister and me. So he sent us off to Mexico as a cheaper alternative. A year later, my father regained his employment and sent back for us.

When I was only five years old, the railroad company my father was working for laid him off. His unemployment check was enough for him to survive, but it did not provide enough sustenance for my mother, my sister and me. So he sent us off to Mexico as a cheaper alternative. A year later, my father regained his employment and sent back for us.

Word soon came to my mother that we had to return, proving to be a challenge because my sister and I were already Mexican citizens. We were able to retain said Mexican citizenship by traveling to the big city and claiming that the town we were living in had simply forgotten to file the proper paperwork; that, along with some monetary compensation to avoid further confusion, sealed the deal. Although we had been birthed in some of Los Angeles’ fanciest community hospitals with a King Taco within walking distance, all of those documents were in Los Angeles.

My father knew better than to send them with any of our relatives visiting the motherland, because he knew they would keep the birth certificates, claim them as lost, and sell them to other folks facing dire immigration straits. Secondly, my father was not going to mail them because he believed the INS would intercept the mail and arrest him, and deport him on fraud charges.

The solution was simple. A plan was devised so that my mother would cross in Tijuana under the guise that she was going to San Diego for a Sunday afternoon punctuated by shopping. My sister and I would cross with my uncle posing as his children and assuming their identities. My mother was praying as much as she was coaching us — because looked nothing like his children. The only thing that was working in our favor was that birth certificates have no pictures. My sister was supposed to play a cousin who was a year older but shared the same name, while I was in charge of impersonating a cousin who was a year older.

My uncle broke down the whole scenario: the immigration official was supposed to take the documentation and ask questions of the adults first and then the children. Our job was to remember our names. He quizzed us with general questions that might come up in the conversations, all the while my mother was praying to patron saints of things and territories I never knew existed.

The line moved slowly, and every time we made progress, we only moved a couple of feet — with each step the praying intensified — and so did the questions. My uncle’s knuckles turned white whenever we gave an answer he deemed too long or too short He stressed that we had to answer in English or risked everything blowing up in our face. My mother would remind him of the pools of sweat that collected on the top of his lip. I don’t remember hearing anything or listening to anyone when I saw that only two cars remained between us and the immigration officer. I kept saying the same things inside my head.

“Your name is Jorge. You like baseball. You were born in Los Angeles. You are in the second grade. Your name is Jorge…

I remember knowing that was not right. There were no more cars ahead of us. It was time to shine. The whole thing went down just as my uncle predicted: the immigration officer grilled the adults about their destination and what their plans were once they got there. My sister was asked her name and how old she was. He then turned his attention to me, asked me what my name was, my age and what I liked doing. Once I told him I liked baseball, he asked about my favorite team. I confirmed it was the Dodgers and he laughed and waved us through.

Once he waved, I never looked back. I remember my uncle kept looking into his rear view mirror. He did not speak or breathe until the officer was a speck on that mirror. He smiled and praised our coach. We had rejoined our American brethren. I could go back to being Oscar. To celebrate that milestone, we did the most American thing we could have done – we pulled into McDonald’s for dinner. Sometimes convenience and Americanism are one in the same.

[Courtesy Photo By Lalo Alcaraz]