My Mean Aunt Socorro Ruled With A Mix Of Fear And Shame

There is one person I always feared when I went to visit relatives in Mexico – my Aunt Socorro.

There is one person I always feared when I went to visit relatives in Mexico – my Aunt Socorro.

She is married to my father’s brother, Rafael, and always insisted on cooking when we spent our summers with my father’s mother in La Rivera, Jalisco. Meals always doubled as a lesson in civility and manners, as she felt that children like us who were raised in the lawless “Norte” were uncouth and ravenous creatures.

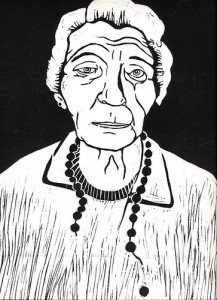

She was a stern woman that looked as if she was built out of bamboo sticks and corn husks. Her legs dragged across the floor as she heaved, delivering every other critical word in a challenged staccato. Her massive frame overshadowed us all. She raised her spoon and served us all in order of her personal relevancy. The adults would eat first and then the older children would serve the younger children.

The main reason why I feared her was because she had all these different rules that seemed arbitrary to me at the time and breaking any one of them resulted in the same threat: a beating with a switch from the backyard. For example, no amount of talking was permitted at the dinner table. Problematic only because I was raised as an American child, and our school teachers and secondary parents always enforced and reinforced the importance of having an open dialogue with our parents. After countless parent conferences, my teachers had beaten down my parents and in particular my mother, that hearing what your kids had to say was a barometer for child rearing. This meant that I was used to telling my mother about my day – no matter how insignificant it was.

In many ways, even my mother was afraid of her and her incessant shaming of others. My mother always fought to be part of my father’s family. For the most part, I think they accepted her, even though they still treated us as an extension of my father. Her name was María, but for so long she was only known as “La esposa de Salvador.” I think she gave up so much of herself in her attempts to simply fit in with them.

Aunt Socorro’s rules of etiquette were hard-learned, as she would leer at you until you fell into a frozen position of self-imposed shame — or else. My aunt had a rule where you could not have your tostadas crunch in her presence. She considered it an ignorant practice perpetuated by ignorant brutes. The crunchy laws of tostadas be damned. This made it much harder for me to eat ceviche.

It is funny how all these figures seem bigger than life, especially when you are a small child. I still remember her endless scoops of crema into my sopa de fideo. I cringed, because my stomach could never handle the purity of Mexican dairy. I hated crema. I would object to the spoon, but she would look directly in my mother’s direction and wonder aloud when certain children would learn to eat, “como la gente.” My mother would coax me into eating the fine mess on my plate as the white cream would become one with the noodles. It was only a matter of time before my stomach would cramp up and the adults would laugh at my digestive disposition.

The last time I went to Mexico, though, I saw her through very different eyes. Disease had taken its toll on my tía. She no longer carried herself with a dominant constitution. In fact, far from it, as the corners of her eyes have yellowed and her once brutal voice is now just a faint whisper. I was amazed by the look she shot at me, as she said “You’re the one who doesn’t eat cream!” She cackled like a truck backfiring while adding, “Muchas hamburgesas…”

Alas, there would not be a heartwarming reunion. There would not be any hugs to strike down past transgressions. In the end, there would only be a wooden woman amongst her own undercurrents of pride holding steadfast to some warped lactose superiority complex.

[Photo By Mar Estrama]