The Rise Of Young Latino Politicians In Texas

It seems like every time you turn around in Texas these days, there’s another young, educated Latino professional with political aspirations who’s either running for office — or just won office. And while it would be easy to say anecdotally that more Latinos are being elected to office in Texas, the facts speak for themselves.

It seems like every time you turn around in Texas these days, there’s another young, educated Latino professional with political aspirations who’s either running for office — or just won office. And while it would be easy to say anecdotally that more Latinos are being elected to office in Texas, the facts speak for themselves.

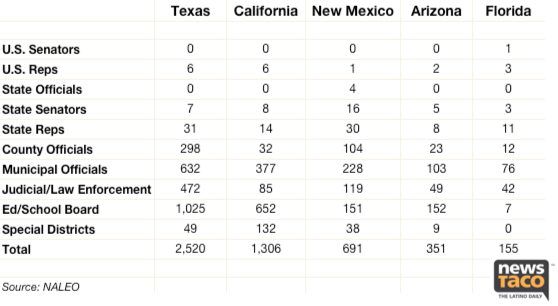

A look at the 2011 directory of the National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials (NALEO) shows that Texas has more Latino elected officials than any other state, more than 2,500, with California’s 1,306 making a not-so-close second. Interestingly, while young Latino politicians seem to be populating the state’s political scene ever quickly, women, or Latinas, don’t seem to be keeping pace — but that’s a story we’ll be telling you in the near future.

But why is this happening?

Demographics have obviously played a role in this new trend — Texas received four new congressional seats as the result of population growth, at least 70% of this growth from Latinos in the state — but demographics alone don’t begin to explain this particular change. We spoke to two young men that may be counted among this trend recently, former San Antonio City Councilman Philip Cortez (left), who has announced his candidacy for State Representative of District 117 and Austin State Rep. Eddie Rodriguez (right) and a few additional reasons that help account for these changes to Texas’ political landscape emerged.

For one, both Cortez, 33, and Rodriguez, 40, were adamant about the debt owed to everyone who came before them. Texas’ sketchy history with civil rights and discrimination is by no means a secret — people not yet eligible for Social Security can tell you stories about “No Mexicans” signs in restaurants — but both politicos have personal and professional experiences to back up their claims.

Citing their parents and politicians who came before them such as former congressman Henry B. Gonzalez, as well as countless other civil rights activists, both men said others had cleared political road for them. Personally for these two, the political mentorship and opportunities afforded to them both in the realms of education and politics would have been practically unheard of for Latinos in Texas even 30 years ago. But, at a cultural level, both noted that the expectation of being able to ascend levels of political power for Latinos across the state came about as a result of the work and struggle of many before them.

“There are people that did all of the legwork in the 60s, 70s and even early 80s that really paved the way for people my age that made it,” Rodriguez told NewsTaco. “There’s almost an expectation that, if you’re Latino and going to college, you can compete with any Anglo person — there’s no reason why you can’t. We have our parents to thank for that.”

Cortez, currently a doctoral student at the University of Texas at Austin, acknowledged the same for himself, but on a larger scale also pointed to the Castro brothers of San Antonio, who attended Harvard Law School, and now Julián is the mayor of his hometown while his brother Joaquín is a congressional candidate in Central Texas. “Educational opportunities have opened up for us,” Cortez said, referencing Texas’ historical struggles with such access, “It’s not a guarantee you’re going to get into these schools without the proper effort — but at least the doors are open.”

Of course neither these two, nor the Castro brothers, and not even the current crop of Latino political candidates — be they city council members, county supervisors, district attorneys, state reps or senators — are the first to come to political power. It’d be disingenuous at best, just as these two Latino politicos noted, to exclude those who paved the way for them. It was members of La Raza Unida, the first Latino mayors and congressman and state reps, voter registration campaigns, and even the solid tradition of Latino elected officials along the border who created the idea that, despite Texas’ spotty record on inclusion, Latinos had just as much a right as anybody else to be in public office.

Fast forward to today and, as Rodriguez points out, there were Latinos in their 20s who were elected to the state house. Opportunities to be elected to statewide office are enhanced by the large numbers of Latinos being elected to school boards, where they may then launch a political career. While this class of young Latino politicos grows, as a group, Rodriguez told us that finding a cohesive political voice becomes a build-the-airplane-while-you’re-flying-it kind of challenge. “Everything is happening in real time,” he told us.

But like everything else, there’s always more that can be done. Both Rodriguez and Cortez said that, as current political leaders following the paths laid down by others, what weighs heavily on their minds now is how to continue to create those opportunities. Teen pregnancy, high school dropout rates, college completion rates, building a diverse and sustainable economy with real jobs, political apathy, building up a Latino middle class in Texas — these are the issues that define their political agends.

“I want to provide a good example, to hope that one day some young girl or some young boy can see the things we’ve done and think, ‘I can do that, too,’” Cortez told us, with a small caveat, “But we still got a long way to go.”

[Photos By Texas House; Courtesy]