One Sailor’s View Of Chile Under Pinochet

In August of 1974, I was an ordinary seaman on board the Margaret Lykes, a merchant ship out of New Orleans, bound for the West Coast of South America. I was 23 years old. Most freighters back then had accommodations for a few passengers, and we had two Chilean couples and their children, going back home. They had been in the United States for the past few years, economic exiles, because of the socialist leanings of the Allende government. Since Allende had been disposed of the year before, and the new right wing government under Pinochet needed all that old blood back, expatriates were offered no duty on any consumer items they brought back.

I couldn’t say how many crates of appliances, cars and household goods these people were shipping back home, but there was more than the average traveler. Or maybe they were just rich, and this was normal. I don’t really know. I didn’t eat mess with these people, they ate with the officers, and we weren’t encouraged to socialize with passengers. I put this all together by a combination of rumors among sailors and my awareness of contemporary events.

The trip was uneventful, except for the time I caught the clap in Columbia, or wandered in the ruins of an ancient village in southern Peru, or saw a man walking a penguin on a leash in the town square, or when we sailed within 85 miles of the eye of Hurricane Fifi on our way back — but these are stories for another time.

We dropped off our passengers and their booty in Valparaiso, Chile, the port for the capitol Santiago. Within a few hours, an American, whom I will call The Professor (because I don’t remember his name), came on board as a passenger for the trip back. He was tall, had a medium build, blonde with blue eyes and was in his 30s; overall he was a pleasant fellow. We were going to be in port for a couple of days, but he came on board right away, and wouldn’t go back ashore. He asked me to run a few errands for him, and he explained that he was in fear of his safety, as friends had recently been disappeared, and he didn’t want to take any chances. He thought the police were looking for him.

The Professor had come down during the heyday of the Allende government, and was a university English professor in Santiago. He had a wife and child, but they had already left for America. He stayed behind to settle their affairs, and was now on the way back to Indiana to rejoin his family. He explained to me about the curfew, to not get caught outside after 10 p.m. or before dawn, because soldiers were ordered to shoot first and ask questions later. I recall doing a bit of shopping the next afternoon, and seeing a homeless man begging a shopkeeper to be able to sleep inside his store that night, because to be outside at night was courting death. The shopkeeper shook his head firmly, and the homeless guy went on down the street.

That’s when I started to notice the soldiers with machine guns, some singly, some in pairs. I got back to the ship well before curfew.

Eventually we headed back north. We returned to Buenaventura, Colombia for a couple of days, and after spending a week there on the way down, it felt like familiar territory. The Professor wanted to see some friends in Cali, which was about 75 miles inland, over the mountains. He rented a cab for the day and invited me to join him. We spent the better part of the day driving to and fro, with a couple of hours visiting his friends. This was long before the War on Drugs turned all this area into a narco nightmare, so there was no fear of driving on back roads over mountain passes.

Then it was back to sea, through the Panama Canal, and around the aforementioned Hurricane Fifi. We dropped The Professor off in New Orleans, and I never saw him again. I hope he had a good life with his family back in Indiana. When I came home to San Antonio, I got served divorce papers from my wife in California. Oh, well.

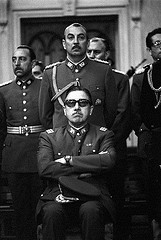

[Photo By Xavier Zaragoza]