Re-Writing Civil War History From Slavery To States’ Rights

[Editor’s Note: This story, written by David Martin Davies, was originally published by the Texas Observer]

[Editor’s Note: This story, written by David Martin Davies, was originally published by the Texas Observer]

EVERY YEAR, AROUND FEB.19, a crowd of tourists gathers in front of the Alamo to watch the re-enactment of a pivotal moment in history. There’s a ragtag company of men dressed like a scruffy 19th-century Texas militia, wearing buckskin and ill-fitting clothes made from homespun burlap. With muzzle-loading long rifles over their shoulders, they’ve copped the appropriate rough-and-ready attitudes. Squared off against the Texan frontiersmen are soldiers from the U.S. Army, sporting cavalry uniforms and blue kepi caps. The soldiers march with precision. The militia lacks the discipline for close-order drills. Both sides are prepared for a bloody confrontation.

This isn’t the re-creation of the most famous battle at the Alamo, but a lesser-known episode from 1861 known as “Twiggs’s Surrender.” The battle took place shortly before the Civil War and illustrated how tense things had become in the state. If fate hadn’t shrugged that day, the Civil War would have begun right here at the Alamo. Maj. Gen. David Emanuel Twiggs was the commanding officer of the U.S. Army in Texas. The Alamo was the supply depot for the state in the effort to protect settlements from Indian attacks and bandits from Mexico. Little did Twiggs realize his most dangerous foe would be Texas settlers.

At last year’s re-enactment, a narrator stood at a podium and told the crowd about Twiggs’s dilemma as the confrontation unfolded. Twiggs had command of a “meager” 160 soldiers at the garrison, and he faced about a thousand “well-armed Rangers and experienced frontier fighters.” According to the narrator, Twiggs had little choice. He was outmanned by the militia and outmaneuvered by the secessionist leaders who called themselves The Committee for Public Safety. The secessionists demanded that Twiggs surrender federal property and armaments under his control—including the armory at the Alamo and 17 forts in the Texas wilderness.

The re-enactors are sticklers for the accuracy of historic uniforms, weapons and gear. There were no Confederate uniforms, flags or insignia in the re-enactment. (The Confederate Army didn’t form until after Twiggs’s submission.) But there were Confederate flags and uniforms not far from the action. They were on display at a table under a shade tree in Alamo Plaza, manned by Russ Lane of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, or SCV.

The organization is one of the organizers of the annual re-enactment, and Lane provided historic background to curious tourists. It’s a version of history sympathetic to the Southern cause. “The Civil War was not fought to free the slaves. The South was fighting for states’ rights,” he said. Lane is a friendly man, and he told his story earnestly. He said events like the re-enactment are opportunities to teach the community what he calls the “truth” of the Civil War. “In school they are not being educated with the whole story. Children are left to think the war was fought to free the slaves and that Lincoln was a great man,” he said.

The re-enactment reached its climax. Actor soldiers called out for action. It looked like a fight. Then Twiggs stepped forward and offered his surrender in exchange for the safe passage of his men out of Texas. The militia men let out a whooping cheer. Women actors in ornate ball gowns celebrated. Tourists clapped and cheered the defeat of the American federal forces and the victory of the pro-slavery secessionists.

THIS YEAR MARKS the 150th anniversary of the Civil War. Each Southern state is grappling with its legacy from a war that killed more than a half-million Americans. Here in Texas, it’s becoming popular to celebrate the war as the opening salvo in the conservative campaign for states’ rights. Neo-Confederate organizations and pro-secessionists are among the leading groups in organizing Texas’ commemorative events. Their version of history downplays the role of slavery in the Civil War and encourages anti-federal government political ideology. They make no bones about it: They’d be happy to see Texas secede again.

Even in conservative Texas, it’s odd that the state relinquishes events like this re-enactment to groups like the SCV. The group has long been monitored by the Southern Poverty Law Center, a nonprofit civil rights organization dedicated to fighting hate and bigotry. “This is the latest episode of these neo-Confederates rewriting history,” says Mark Potok, the director of the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Intelligence Project. Potok said the SCV frequently portrays itself as a group that promotes Southern heritage and history. Potok said they are actually a white-supremacy, neo-Confederacy group that seeks to revive pro-Confederacy sentiment. “They want people to think the war had nothing to do with slavery.”

Potok said the group is using media attention to the war’s 150th anniversary to grandstand across the South under the guise of teaching history. On Feb. 19, a week after the re-enactment of Twiggs’ Alamo surrender, hundreds of Civil War re-enactors will parade up Montgomery’s main street to Alabama’s state Capitol to recreate the swearing-in of Confederate President Jefferson Davis. The Southern Poverty Law Center is joining civil rights leaders and the NAACP in condemning the celebration as an offensive event that sanitizes history.

The neo-Confederate groups openly say that slavery wasn’t as bad as people make it. Russ Lane of the SCV said reports of atrocities against slaves were exaggerated. “I didn’t live through it, but it doesn’t make sense for someone to whip their own private property,” he said. Lane said that in the early 1860s, photography was available and that while there is some photographic evidence of scarred backs of beaten former slaves, there should be more proof if whipping was widespread.

“The Sons of Confederate Veterans are the Holocaust deniers of American history,” said Michael Phillips, professor of History at Collin College in Plano and the author of White Metropolis: Race, Ethnicity and Religion in Dallas. “They have undertaken a long and deliberate campaign to whitewash our history—I deliberately said ‘whitewash.’ The Sons of the Confederate Veterans offers a version of history that makes great theater and does shape the public’s understanding of what happened during the Civil War.”

North Texas history professor Randolph B. Campbell said each year he faces college students who insist that the Civil War was fought over states’ rights. “Sure, the states’ right to allow slavery,” he said. Campbell has written eight books on the Civil War and Reconstruction, including An Empire for Slavery: The Peculiar Institution in Texas. Campbell said there is no debate about the facts. When Texas broke away from the Union, it issued “A Declaration of the Causes which Impel the State of Texas to Secede from the Federal Union.” The document says Texas “was received as a commonwealth holding, maintaining and protecting the institution known as negro slavery—the servitude of the African to the white race within her limits—a relation that had existed from the first settlement of her wilderness by the white race, and which her people intended should exist in all future time.”

THE TEXAS HISTORICAL COMMISSION could be taking the lead on commemorating Texas’ role in the Civil War. By allowing the Sons of Confederate Veterans to use Texas historic sites for its re-creations, the commission gives the impression that the events have tacit approval from the state.

The Historical Commission is taking a low-key approach to recognizing the Civil War’s sesquicentennial. It is focused on two events, the May 1865 Battle of Palmito Ranch, the last major battle of the Civil War (fought in Brownsville after Lee surrendered), and 2015’s Juneteenth in Galveston, which will celebrate emancipation.

William McWhorter, Texas Historic Commission program coordinator, said the commission is facing two challenges with the Civil War sesquicentennial. First, the state has a tight budget, and there might not be enough funds for special programs. And the sesquicentennial comes the same year that Texas celebrates its 175th anniversary of independence. The commission will have three regional “Sesquicentennial of the American Civil War Workshops” this year in Austin, Laredo and Tyler. The workshops are being financed by a grant from the Society of the Order of the Southern Cross, a nonprofit dedicated to the “preservation of Southern Heritage through Confederate philanthropy,” according to its website. It’s hard not to wonder how balanced these workshops will be.

Of course, no matter how well-intentioned, any reenactment or retelling of history will have its own angle. Jesus Frank de la Teja, former state historian and a Texas State University professor, says the commission “is not the state’s history police.” He says historical research and writing is a dialogue between the present and the past. “Demographic, economic and social change will take care of popularly held memories—whether intentionally fabricated or spontaneously created. We live in a land of free speech, but free does not mean correct.”

And in another week, Twiggs will once again fail to make a stand at the Alamo. How will history judge the man? Was he a hero or a villain? “Neither,” said historian Campbell. “He was just a human being caught in a really bad situation.”

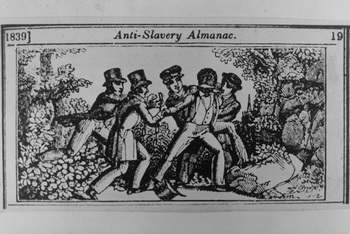

[Image Courtesy Leslie]