How Do You Say ‘Thanksgiving’ in Spanish?

When I was a kid in the 1950s, we still spoke mostly Spanish at the homes of our extended family, and we called it “Día De Dar Gracias.” At the time, there was still confusion about when Thanksgiving would be. My father would have Thursday and Friday off work on one week, and we would be out of school on another. But we managed.

When I was a kid in the 1950s, we still spoke mostly Spanish at the homes of our extended family, and we called it “Día De Dar Gracias.” At the time, there was still confusion about when Thanksgiving would be. My father would have Thursday and Friday off work on one week, and we would be out of school on another. But we managed.

But as I grew older, local radio announcers — almost all of them arrogant recent Mexican immigrants who considered themselves celebrities and who often looked down, disdainfully, at our local Spanish — started saying it should be “correctly” referred to as “Día de ACCION de Gracias.” Not that it mattered to me. I only looked forward to the family feast, which would assemble most of my mother’s family into a tiny kitchen to chow down and sit around and enjoy the fact that we were all together and eating very well.

Our regular diets at the time included fewer animal products, and even then, not really great animal parts. I was probably 20 when I first tasted a tenderloin, and 30 when I first bit into a lobster. We did with what we had, which included great “specialty meats,” like beef hearts, liver, kidney and mollejas (that I still relish, and which are actually thyroid glands), chicken livers and gizzards, and all parts of the pork except the “oink.”

Even though most of my family were involved in raising animals, of some sort — from backyard chickens to cattle — we ate a lot less meat and far more fresh vegetables, often from our own gardens, and a healthy mix of fibrous starches and proteins. Two staples remain major components of my diet today, arroz y frijoles (or habichuelas as they are in some places called) made, of course, with appropriate vegetables — chiles, tomates, ajos, cebollas, (y ahora, el Mr. Gourmet even uses shallots), and when available, cilantro and epazote.

But Día de (Acto or not) Dar Gracias would be when the extended family would gather at a crowded table to, as they say, break bread. But there would be little bread to break. One of the tías might bring a package or two of brown-and-serve rolls from the grocery store. But tortillas were still the mainstay, both corn and flour, giving us all, I suppose, freedom of choice. And we didn’t eat turkey, which at the time was to us, an unaffordable luxury. We would settle for one or two over-sized chickens.

But Día de (Acto or not) Dar Gracias would be when the extended family would gather at a crowded table to, as they say, break bread. But there would be little bread to break. One of the tías might bring a package or two of brown-and-serve rolls from the grocery store. But tortillas were still the mainstay, both corn and flour, giving us all, I suppose, freedom of choice. And we didn’t eat turkey, which at the time was to us, an unaffordable luxury. We would settle for one or two over-sized chickens.

And we would feast on more familiar special fare, like pork ribs adobadas with dried chiles, garlic, comino and salt and pepper, slowly baked until the meat was falling off the bones. Or we might have beef ribs, less spiced but likewise cooked. And if someone had shot a deer illegally, we might have a piece of that roasted, and everyone would rave about it even if it was tough and tasteless, if not gamy.

There would, of course, be rice and beans. How could one do without that? And salsas, frescas and rancheras, green and red, made with fresh chiles from some relative’s backyard garden. And by November, there would also be some cilantro to throw in.

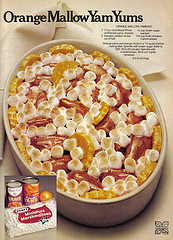

And the aunt who subscribed to some American “ladies” magazine who would bring a horrid concoction of sweet potatoes baked with melted marshmallows atop. She would also bring cans of bright red, cartilaginous cranberry sauce that would be emptied out, in their cylindrical form — with the ridges from the cans plainly showing — onto plates that everyone would politely take a slice off. “¡Porque es Thanksgiving!”

Not that anyone knew what to do with the cranberry stuff, or where to smear the jam. I remember an uncle saying, “Pues no sabe mal con mantequlla” after slathering some on a flour tortilla.

Not that anyone knew what to do with the cranberry stuff, or where to smear the jam. I remember an uncle saying, “Pues no sabe mal con mantequlla” after slathering some on a flour tortilla.

But very quickly, I started seeing the advance of America’s culinary cultural imperialism creep into out lives. Cornbread soon became a part of the feast, and after some Anglo lady shared a recipe for it with an aunt, dressing that included country sausage — and so did it.

When turkey became more affordable, I recall my mother roasting one, and making giblet gravy, though the camotes con marshmallows never improved. The turkey, was, and usually remains, a dry, stringy mess that must be drenched with some liquid to make it palpable, but everyone continues to praise its specialness.

Over the years, turkey — America’s great bird that has now become so hybridized that virtually all of them must be artificially inseminated because their breasts have so grown, even on the toms, that they cannot reach their ends — became a Thanksgiving staple in our homes. But it never replaced my family’s more favored costillas de puerco adobadas, and the dressing I now make is made with leeks, oysters and shitake mushrooms instead of country sausage. Inevitably, someone will show up to the family confab with a pan of overcooked green beans topped with canned fried onions, and someone will also bring yet another horrible concoction of camote con marshmallows. Thankfully, no one shows up with a shoulder of gamy deer any more.

But there will always be the arroz y frijoles, the salsas, and the fellowship of a family growing farther apart, and missing those who are no longer with us, and wishing we had learned from the departed tías how they made this or that. We truly relish seeing each other. Distances and time, I have learned, will do that.

And that is what Día de (Acto or not) Dar Gracias is to me.

Oh, and could I get another slice of that German chocolate cake? And no, I haven’t the slightest idea how that became part of the feast.

[Images Courtesy tuchodi, jbcurio and scaredy_kat]