Latino students missing school for vacation deserves more scrutiny

By Esther J. Cepeda, NBCLatino

By Esther J. Cepeda, NBCLatino

This also happens at the beginning of the school year and during the holidays as parents take their children out of classes for long family trips. But I can tell you from first-hand experience that there’s nothing worse than getting through the post-spring break blahs and pushing hard to end the year strong, only to have students drop like flies before you reach the finish line.

Understand that I’m not talking about children of farmworkers whose families follow the harvest. I turn your attention to students of families who are financially stable enough to travel for pleasure — or at least can afford it when the need arises — and can do so legally.

When I last surveyed administrators in the Chicago Public Schools system in 2007, they said that although the Hispanic attendance as students returned from Christmas vacation was still bad, it was improving. An unfortunate combination of increased violence in Latin America and intense border security crackdowns had bolstered their own targeted outreach to parents about the importance of keeping students in class throughout the entire year.

Indeed, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, the percentage of eighth-grade Hispanic students who reported missing three or more days of school in the previous month decreased significantly from 1994 to 2011 (from 27 percent in 1994, to 21 percent in 2011). And attendance among Hispanic fourth-grade students in these groups remained stable from 1994 to 2011.

These numbers don’t indicate whether the absenteeism is clustered around the first and last weeks of school or vacations. Nor am I trying to imply that non-Hispanic students don’t also miss school as well. But note that the highest performers in schools today, Asian and white students, also happen to have the lowest absenteeism rates. In 2011, only 11 percent of eighth-grade Asian/Pacific Islanders and 18 percent of white students reported missing three or more days of school in the previous month.

Still, the sheer number of Latino students in public schools — one out of every four elementary school students — and their distinctive pull toward extended family, not to mention high dropout rates, demand that these types of absences get more investigation.

Based on what I’m hearing and seeing, it’s now the students of families who have the proper papers to move freely between two countries who are most likely to skim a few days off school here and there. But while those numbers may be smaller than in the past, the stakes are higher. Many schools now have strict policies regarding such absences, which take them from the level of annoyance to a real opportunity for failure.

In my majority-Hispanic school district, the policy is clear and tough: “Vacations during the school year are not a valid cause for an absence and will be considered unexcused. Students will be disciplined for unexcused absences.” And, yes, students fail courses when they miss finals.

Strangely, the whole issue is largely taboo. Of the many teachers I’ve talked to about their experiences with Hispanic student attendance, none wanted to be named for fear of being labeled as culturally insensitive.

One educator, who is himself Hispanic and works mainly with Latino students, told me, “From a cultural perspective, I have too many parents disregard school with ease if it does not fit into their holiday plans. Students are always most successful when parents support their kids academically. I realize this is obvious, but if a kid misses on finals or school for an extended period of time, that is the opposite of supporting your kids academically.”

Daniel King, superintendent of the Pharr-San Juan-Alamo Independent School District near the Texas border with Mexico, verified that he’s seen a drop in such absences at his schools since border security was tightened. But he was unsure what would happen if immigration reform gave those living here illegally a Registered Provisional Immigrant status that would allow them to easily travel outside the U.S.

“I hadn’t really thought of that to be honest with you, but I can see where that might make it more of an issue,” he told me.

Trust me, it’ll be an issue — so let’s start talking about it.

This article was first published in NBCLatino.

Esther Cepeda is a syndicated columnist and an NBC Latino Contributor.

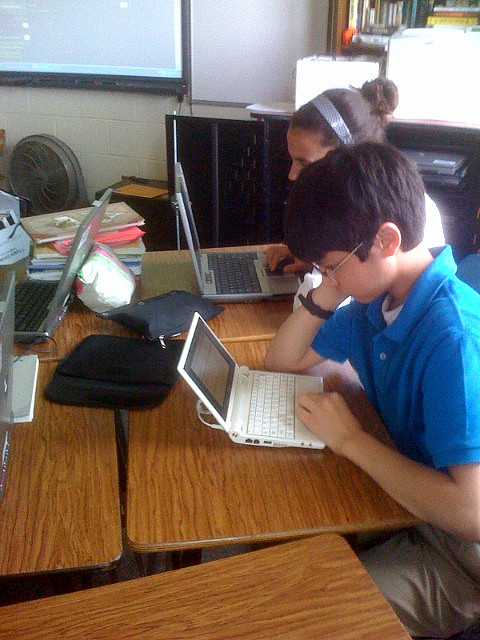

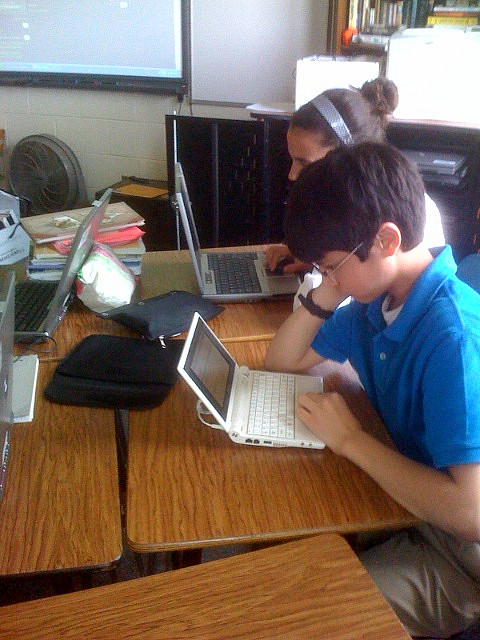

[Photo by USM MS photos]