Día de la Revolución: Pancho Villa and My Grandfather

By Tony Castro, Voxxi

By Tony Castro, Voxxi

“He wasn’t yet Pancho Villa,” my grandfather used to say when he would tell the story. “He was Arango. Jose Arango, and we met when he came to our stable to sell his horse. He was starving, wounded and hadn’t slept in days.”

“He didn’t know it, but he had come to the one house in Chihuahua that would welcome him with open arms. The federales had taken all our horses the year before and paid my father only a fraction of what they were worth.”

“He didn’t know it, but he had come to the one house in Chihuahua that would welcome him with open arms. The federales had taken all our horses the year before and paid my father only a fraction of what they were worth.”

“’Keep your horse,’ my father told him. ‘And come inside. Eat and rest. We’ll doctor your wound.’”

It was 1903. Arango, who had lived briefly in Chihuahua already had a reputation as a bandit and an outlaw, but had been forced to join the federal army just months before deserting, killing the officer and fleeing.

“I nursed his wound, fed him, and he trusted my father and trusted me,” my grandfather recalled. “’You and I are tocayos!’ he told me.

I didn’t know what that was. I thought he meant we were outlaws. Imagine how silly I felt when I learned it only meant we shared the same Christian name.

The birth of Pancho Villa

“But he said we weren’t to call him Jose Arango. He had decided that he was going to be Villa, after one of his grandfathers. It was as if Francisco ‘Pancho’ Villa was born right there under our roof.”

My grandfather would tell these stories about Villa from time to time, but most often on November 20—el Día de la Revolución—when he would commemorate with other Mexican immigrants at a yearly celebration on Calle Dos, a name given to a Mexican area of my hometown in Texas.

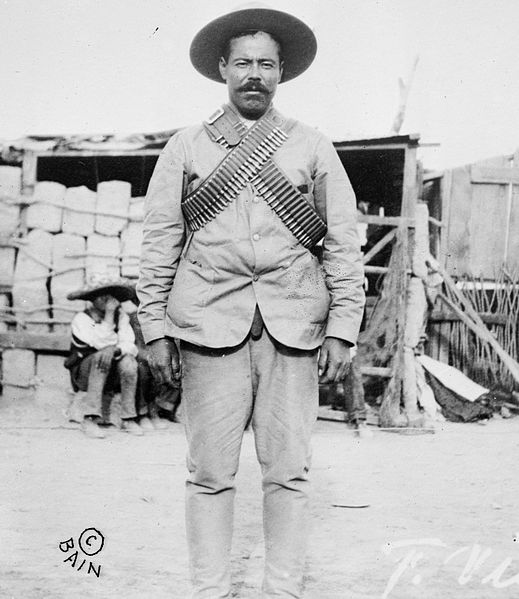

On the day of those festivals, my grandfather would wear an old leather bandoleer over a double-breasted pinstriped suit. The bandoleer was always empty, as he would remove the bullets and leave the ammunition in his home.

But he was a sight, and those were the only days that I also saw him sporting an old Mexican sombrero like the kind you see on faded photographs of Villa. My grandfather had a wrinkled sepia picture of Villa with several young men, one of them he said was him.

“Villa was a man, the rest of us boys,” he would say when he would show the photograph. “We were boys learning to be men.”

Villa returned to Chihuahua numerous times to take shelter with my grandfather’s family, sometimes sleeping in one of the stables, according to my grandfather.

“Villa was still a bandit, but he was the kind of bandit who would rob from the hacienda owners and give what he stole to the people.”

The Mexican Revolution

It might have stayed that way, my grandfather said, with Villa more of a Robin Hood had he not finally connected with Francisco Madero, the politician who many credit for fathering the Mexico Revolution against dictator Porfirio Diaz.

By 1910, when the revolution began, my grandfather was riding with Villa in his mounted cavalry troop that came to be known as the División del Norte.

I was a young boy when I first began hearing these stories from my grandfather and, understandably, developed romantic notions of what this revolutionary period might have been like.

My grandfather, however, was always careful to caution that the revolution had been ugly, like most wars. His family eventually had to flee Mexico, and there were numerous times when he talked about being on the run from setbacks that the Villa troops had suffered.

The most serious of those setbacks occurred in April of 1915 at the Battle of Celaya where my grandfather suffered a serious leg wound. By then he had made several crossings into South Texas, according to border entry records. He made his final crossing that May, joining his family to be nursed back to health.

My grandfather never returned to Mexico, even after the end of the revolution, which is often said to have ended in 1920, though fighting continued into the decade.

“If you’re a true Mejicano,” my grandfather used to say, “the revolution will never be over.”

This article was first published in Voxxi.

Los Angeles-based writer Tony Castro is the author of the critically-acclaimed “Chicano Power: The Emergence of Mexican America” and the best-selling “Mickey Mantle: America’s Prodigal Son.”

[Photo by Bain News Service, Wikimedia]