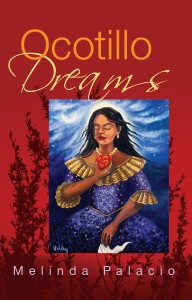

“Ocotillo Dreams” A Poetic, Political, Riveting Novel

Melinda Palacio’s novel, Ocotillo Dreams (Bilingual Review Press, 2011) is an intrepid first novel fashioned with the ocular chops of a poet, and the restraint and rhythm of a mid-career griot. At the center of the novel resides an egregiously racist police action that occured in Chandler, Arizona in 1997. The Chandler Roundup was an aggressive program of arrest, detention, and deportation of hundreds of undocumented workers by a joint task force of federal Immigration agents (I.C.E. now, then I.N.S.) and local Arizona police.

Melinda Palacio’s novel, Ocotillo Dreams (Bilingual Review Press, 2011) is an intrepid first novel fashioned with the ocular chops of a poet, and the restraint and rhythm of a mid-career griot. At the center of the novel resides an egregiously racist police action that occured in Chandler, Arizona in 1997. The Chandler Roundup was an aggressive program of arrest, detention, and deportation of hundreds of undocumented workers by a joint task force of federal Immigration agents (I.C.E. now, then I.N.S.) and local Arizona police.

Ocotillo Dreams depicts great reversals of fortune, but the novel doesn’t laud anyone’s ledger. Politics relating to U.S. Immigration policy play a prominent part, but Palacio is not didactic or fervently myopic, and she’s not looking for converts. She’s here to tell her randy little yarn, to delineate the contours of characters that are invisible and unsung to most people. In fact, many of Palacio’s characters might not have their papers, or mica, but they are made flesh and bone by Palacio’s stylus.

This does not mean that Palacio’s novel is pitch perfect or entirely balanced; the novel is divided into three sections, “The House, The Sweep, Ocotillo Dreams.” The section titled “The House,” dominates the narrative, both because Isola, the main character, has come to Chandler, Arizona to sell her mother’s house who has just passed. This section serves as the actual foundation of the narrative — it “houses” the major conflict between Isola and her mother Marina. The subsequent sections struggle to find the depth of the first section, and they never entirely reach it.

Yet, the novel exudes myriad perspectives, and manages to frame the event through the eyes of several key players like Bill Davis, the owner of a furniture factory that periodically doles out work to undocumented workers and is targeted in the Roundup by local police and federal INS agents. Like most unscrupulous Americans in the manufacturing racket, the allure of undocumented labor is just too strong. Sometimes, the owners of factories are even in on ICE/INS raids,

Usually INS handled the illegal raids and Bob accepted his cash and took the men who weren’t pulling their weight. INS bagged their illegals, the temp agency sent him better replacements, Bob made some pocket change for his wife and kids, and the men they deported crawled back and begged for their jobs in six weeks (pg. 130).

Another key player, Doña Trini, lords her legal status as a U.S. citizen over the undocumented that come into her orbit. To avoid her nephew, Óscar, getting nabbed by an INS task force, Doña Trini narcs on a pregnant woman she believes is illegal.

Mira, why don’t you take the woman from the last house on the street? The one with the red rocks in the front yard. She came over here just to have her baby.

Palacio weaves in and out of the narrative, at times lending the novel a cinematic arch, an aftertaste that made me think of movies like Traffic (2000) or La Misma Luna (2007). Palacio starts the novel in the present and works her way backwards, cluing the reader in on vital interactions between Isola and Marina. At the same time, the novel is very much about how the child grows into the parent, whether they want to or not. Ocotillo Dreams also seems to be about the history of our future we can’t escape.

The current xenophobia exhibited by the state governments of Arizona, Alabama, and Georgia inflict an inexorable psychic pain on Latinos. These states say with their actions that people of color are suspect, and that we should be suspicious of them. Publishers are typically wary of novels that use these episodes as their backdrop. But, there are many novels with a clear political bent (1984, Slaughterhouse-Five, Heart of Darkness) that address the psychic pain inflicted by facism, racism, and commercialism. Palacio’s novel proves that you can utilize fiction to make sense and meaning of terribly spiteful and racist events in our country’s history.

[Photo Courtesy Bilingual Review Press]