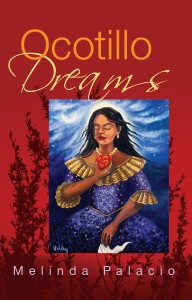

Reimagining The West In The Novel “Ocotillo Dreams”

On Saturday the September 17, the Autry Museum in Los Angeles hosted a book talk for Melinda Palacio’s new novel, Ocotillo Dreams (Bilingual Review Press, 2011). If you are not familiar with the Autry, then there is still a sliver of Los Angeles that remains elusive to you.

On Saturday the September 17, the Autry Museum in Los Angeles hosted a book talk for Melinda Palacio’s new novel, Ocotillo Dreams (Bilingual Review Press, 2011). If you are not familiar with the Autry, then there is still a sliver of Los Angeles that remains elusive to you.

Across from the Los Angeles Zoo in Griffith Park, the Autry, a squat adobe megabuilding, exists to preserve the memory of the American West in all its iterations. The museum is daily thronged with European tourists who come to Los Angeles seeking its frontier secrets, and western ether; and, many of its operational hours during the week are spent shepherding classes of elementary and middle school kids through its halls. But, the museum is heavily vested in the cultural life of the west as well, and this was evident from Palacio’s book talk and reading.

The book talk was held in the Romance Gallery which contains many dynamic renditions of typical western landscapes; the landscapes represent several scenes of pioneer life, and the western quotidian. These antiquated scenes of western life presented a striking backdrop for the book talk concerning Palacio’s novel, since her debut novel takes place in Chandler, Arizona during the time of The Chandler Roundup, a repressive law enforcement aggression against undocumented workers that resulted in the deportation of several hundreds in 1997. The main character’s mother works for a pro-immigrant group that assists immigrants to cross the desert safely and without the use of coyotes.

Palacio commenced the talk by speaking of the antagonistic relationship between the mother and daughter characters, Marina and Isola, in Ocotillo Dreams. Palacio recounts that initially she found it difficult to write about her mother, who had recently passed away when she began to write the novel, and that her relationship with her mother was the polar opposite of the relationship between the mother and daughter in the novel. Then, Palacio spoke briefly about how publishers attempt to confine writers by asking them to choose between being fiction writers or poets. To illustrate this discrepancy, Palacio read a poem called “Abuela’s Higuera,” from Folsom Lockdown, a chapbook published by Kulupi Press in 2009.

The words eeked out as she read the graphic introduction to her prose poem (“Abuela’s Higuera”), and leaned into the microphone:

I remember the time your father was trying to kill my daughter with a brick. Beneath the shade of my fig tree, he beat her. She stood there, letting him slap and punch her. Your abuelo told me to stay out of it. But if it weren’t for me, the good-for-nothing would’ve killed mija with a brick.

As always, Palacio’s work as a writer is loosely based on her life, but is decidedly not a depiction of it. Many people can’t wrap their heads around that distinction, but Palacio seems comfortable to work in that nuance of experience.

On my way out the kitchen door I grabbed my rolling pin. He didn’t even see me coming when I whacked him on the head. I would’ve finished him off with his own brick if your mother hadn’t stopped me.

Maybe it’s because Palacio is unafraid to use her personal experiences as fodder for literature, and texture for her poetry. Palacio is that rare breed of writer that is not afraid to thrust their life into their art, and vice versa. Furthermore, although Palacio is not necessarily didactic, her characters learn how to live symbolically; they learn to inhabit their skin without zero apology.

After that happened, the sad fig tree didn’t give good fruit anymore. Only these dried little nuggets with sticky milk. We had to wait a whole year for the fig to produce again. Your father ruined the tree. My poor higuera.

Palacio wrapped up the book talk by reading the prologue of her novel, Ocotillo Dreams. It provided a fitting denouement to the event, and gave me great reassurance that the culture of the west is still alive and well. The idea of the west has gone through several iterations and renditions. Each of the media that interpreted the west (movies, television, and radio) have also helped to shape its current form. Hearing The Lone Ranger was a much different experience than watching it on television. And, yet, both have their place. Palacio’s novel extends the dialogue concerning the west into the next century by using an old technology, like fiction writing, to say something of importance about the current tide of Nativism and ethnic chauvinism in Arizona.

[Photo Courtesy Bilingual Review Press]