If You Speak Spanish In The U.S., Thank A Pocho

Que desgracia que haya Latinos en este país que no hablen español. It’s a shame that there are Latinos in this country that don’t speak Spanish.

Que desgracia que haya Latinos en este país que no hablen español. It’s a shame that there are Latinos in this country that don’t speak Spanish.

I think it was the Dominican producer talking to her Venezuelan co-worker who said that. I was a half-step behind, following them through the halls of a television studio in Miami, on my way to do a guest shot on Univisión’s “Al Punto.”

They were immigrants, which is not their fault – recently arrived, and luckily landed on a pretty good gig prepping guests for the Sunday morning Spanish language issues program, taped on Friday. They were young and filled with their own sense of certainty, and they had no concept of the long history of Latinos in the U.S.

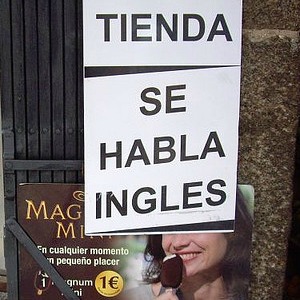

The conversation had started moments before when I muttered something about the variety of Latinos in this country: recent arrivals, multiple generational, varying language capacities and countries of origin. The majority, I said, are Mexican-American and many of us don’t speak a word of Spanish. We were walking already, and they were incensed.

¿Como es possible? No saben el daño que le hacen a sus hijos al no hablarles español. How dare anyone not speak español.

These were professional journalists, mind you, encumbered by their chosen profession to be objective and weigh things within their particular and specific context.

I thought of my mother, a Tejana who married a Mexican man and followed him to live in Mexico. She was belittled by some in her new Mexican family, my cousins and aunts and uncles, because of her pocho Spanish. Mom endured their laughter, asked for the correct way of saying what she had just mangled and slowly perfected her fluency.

There’s a part of the Latino surge that we don’t talk about too much. It has to do with the condescending attitude of some, not all, Latin American immigrants who feel a sense of disdain for Chicanos, pochos, who they consider a watered-down version of “legitimate” Latino. I ran into this a lot in my days as a Spanish language journalist. It was a certain sense of entitlement of Mexican or South American reporters who felt a slice above native, English-dominant, Latinos.

What you don’t realize, I told the Univisión producers, is that those pochos have been busting their backsides for generations in order for you to have the liberty to say what you just said. We’ve been fighting political and cultural and economic battles for decades. You can’t stand here, fresh off your flight from Caracas and judge what you don’t know.

Okay, I was a little perturbed and if my voice were solid it would have left a mark. The two women said nothing more.

There was a time in San Antonio, in Spanish language television, when viewership was determined by counting UHF antennas on the roofs of houses on the West and South sides of the city. The Univisión station (channel 41 back then was part of the S.I.N. network) was the only one on the UHF dial, so the only reason for a family to put a UHF antenna on their roof was to watch Spanish television. Spanish TV was invisible to the Nielsen ratings company. We were considered second-class broadcasters. Now Univisión is a powerhouse and the swagger in the halls is understandable. But it wasn’t always that way – it’s been a grueling journey.

Pochos have fought the good fight, paved the way, made the Spanish media of today possible so that a pair of producers from Venezuela and the Dominican Republic could walk the halls of a pretty good gig and lament the lack of Spanish among native born Latinos.

Si supieran, I said. If you only knew.

In the studio Jorge Ramos greeted me with an abrazo – we’ve known each other for many years, although we hardly, if ever, cross words.

¿Como están las cosas en San Antonio? How are things in San Antonio?

La lucha continúa, I said. The struggle continues.

Follow Victor Landa on Twitter: @vlanda