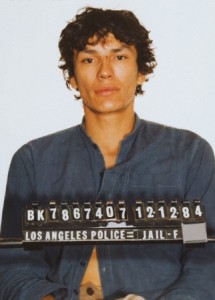

The Hot, Sweaty Summer Of Richard Ramirez

The summer of 1985 was a particularly hot one — and not just because of the weather.

The summer of 1985 was a particularly hot one — and not just because of the weather.

Everyone forced themselves to suffer the indignity of staying indoors. After all, there was a psycho killer on the loose. His name was Richard Ramirez.

Ramirez had everybody scared, even though many people were not ready to admit it. The viejitos ran indoors as if the sun was chasing them. My friends and I were banned to return outdoors after suppertime. Even the homeboys that would kick back at the end of the block made sure they would go back indoors before the sun began to set.

We were all sure that, if we could only stay in the sun or inside, we could avoid become his next victim.

Ramirez had everyone spooked because, for a time, it seemed as if he would strike at a whim. And for a second there, he seemed unstoppable. My father read his copies of La Opinión as if they were God’s privately versed gospel. In addition, my dad also hung on Eduardo Quezada’s every word on Canal 34 – all in an attempt to forecast the next murder.

Criminologist theories were forged by prehistoric bloggers who did not have access to computers then. Fact and rumor were undistinguishable, so they went with what felt stranger than fiction.

And the rumor was this: Ramirez targeted yellow houses in desolate neighborhoods located off the freeway.

Our family happened to live in 122 Bodie St. which used to be a friendly enough neighborhood, despite the fact that said neighborhood was located in an alley darker than Ronald Reagan’s heart. That street was so desolate, it does not even exist anymore — it barely did then. The only way Domino’s Pizza would deliver to us would be if someone was willing to meet the driver at the Shell gasoline station on Boyle and First.

What had my dad scared even more was that our house in this dark alley happened to be yellow.

My father was willing to paint the house if our landlord was willing to put up the paint. The landlord did not budge; instead he suggested that we get a dog. We capitulated. But the dog did not do anything. My father spent afternoons feeding it chiles in an attempt to toughen it up. All the dog would do was bark at other dogs and scratch the backdoor when the winos on the alley got too loud, which is to say, the dog would be useless against a cold blooded killer like Ramirez.

As if having a yellow house in a desolate neighborhood with a lame dog was not enough, the hat trick was completed by the fact that our house was perfectly placed at the exit and entrance of the 101 Hollywood Freeway. Maybe we ought to have purchased a banner reading, “Take our lousy crap. Kill our worthless household pet, but please leave the VCR.”

That summer, the temperature and the body count seemed to rise as if they were in direct competition with one another. There was no end in sight for either. My parents and uncle lost sleep. My father and uncle would take turns battling insomnia in their underwear and sit on the porch, bat in hand, waiting for Richard Ramirez.

As my summer vacation evaporated, news of Ramirez’s capture began to flood television screens. It did not surprise me that they caught him in East Los Angeles, since I was sure we were not the only neighborhood that over-prepared for his arrival. The other part that did not surprise me was the fact that a vigilante mob beat him to an inch of his life.

Rather, the part that surprised me was the fact that every neighborhood in East Los Angeles took credit for at least getting a shot to the head. Even Satan’s self-appointed favorite disciple has a chance in hell when it comes to outrunning a mob of angry Mexicans in East Los Angeles. Everyone claimed that they were part of the posse including my father and uncle who went as far as to claim that our useless dog took a chunk out of his ass.

I kept my father’s secret, although I knew in my heart that the dog was much closer to Charlie Brown than Charles Bronson.

Follow Oscar Barajas on Twitter @Oscarcoatl

[Photo By LACSD]